10 Dec 2025

This fall I was nominated in the Rising Star category for the 2026 State Council of Higher Education for Virginia’s Outstanding Faculty Awards! As part of the nomination process, I had to solicit letters from supervisors, colleagues, students, and community leaders. Several letter-writers graciously shared their letters with me. What a treat! Regardless of whether I’m selected or not, I appreciate having a stash of letters I can turn to next time I’m feeling blue.

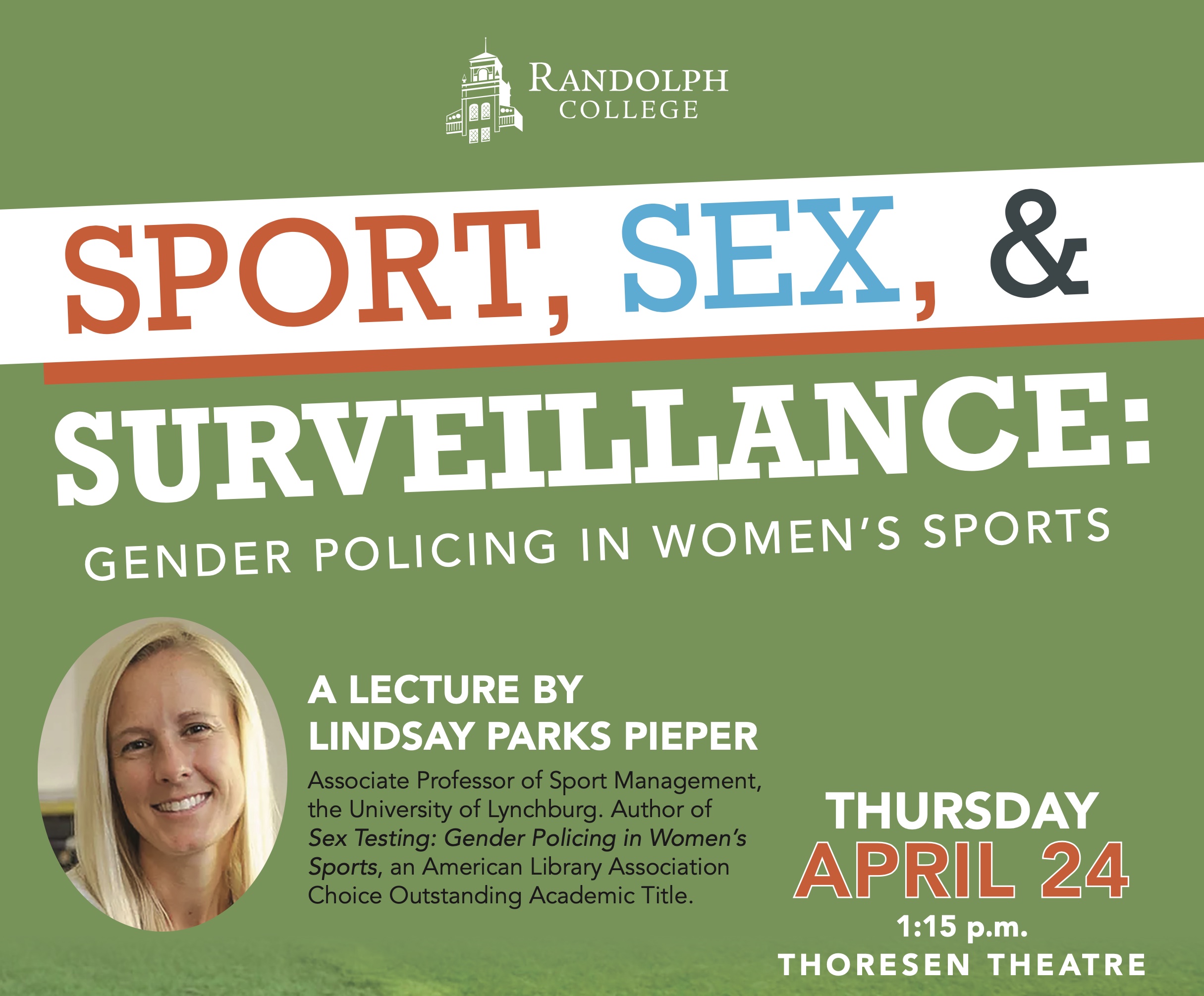

A few months earlier, the image below appeared on the college’s homepage. I was hoping my 15 minutes of fame would be a little cooler, but you take what you can get, I guess!

15 Nov 2025

This past spring, Admissions asked me to give a “sample class” for an Admitted Student Day. I decided to create a version of historian Cate Denial’s “What Do Historians Do?” exercise. It’s a fun activity for the first day of class because students think it is just a fun game but later realize the activity helped them think critically about narrative, evidence, and the archive. I thought it’d work well in this setting because it’s engaging and students don’t need to know anything about the topic prior to the exercise. The exercise makes clear to students that if they come to Randolph, they won’t just be memorizing – they’ll learn to become critical thinkers.

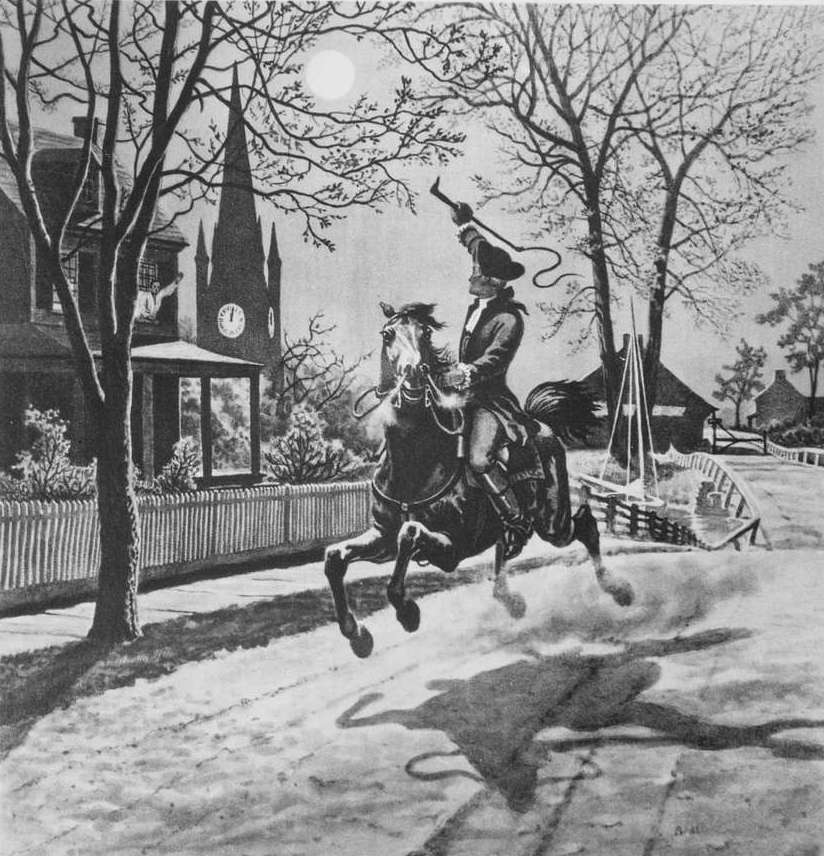

To set up the exercise, I decided to talk a little about the Revolution and how historians have told it in different ways at different times. Ms. Llewellyn, my fifth grade teacher, would be proud to know that I opened my talk with the first two stanzas of Henry Wadsworth Longfellow’s “Paul Revere’s Ride” – all from memory! After making fun of myself for clearly going to school in the 1900s, I have them do a little math to calculate that this is the 250th anniversary of “the eighteenth of April in (seventeen) seventy-five”.

I give them a heads up that they’re going to hear a lot about the American Revolution over the course of the next year. But I insist that telling the story isn’t just a matter of regurgitating facts. We have to tell the story; and in doing so, we’re making choices (whether we realize it or not) about what stories to include and how to frame them. How you tell the story of the Revolution shapes the contemporary lessons people draw from it. Is the Revolution about the evil of taxation… or about the necessity of overthrowing autocratic rulers? Well, it depends on how you tell the story. How we tell the nation’s origin story shapes how we think about our country in this moment.

I then pivot back to Longfellow’s poem. Like most people, I learned the poem in the Revolutionary War unit of my elementary history class. But that wasn’t when it was written. As I have since learned, the poem was published on the eve of the Civil War as Southerners had begun to secede from the union in order to preserve the institution of slavery. Longfellow was an ardent abolitionist. In other words, I’ve come to realize that the famous poem wasn’t just about Paul Revere. It was a powerful call to arms for the Union:

A cry of defiance and not of fear…

In the hour of darkness and peril and need,

The people will waken and listen to hear

The hurrying hoof-beats of that steed,

And the midnight message of Paul Revere.

The story of the Revolution isn’t just about the past; it has ramifications for us in this moment. I tell the students that unlike Henry Wadsworth Longfellow (who played fast and loose with some facts), historians use evidence to tell us what happened… cue transition to analyzing a set of Revolutionary-era political cartoons and coming up with the narrative they elicit!

10 Oct 2025

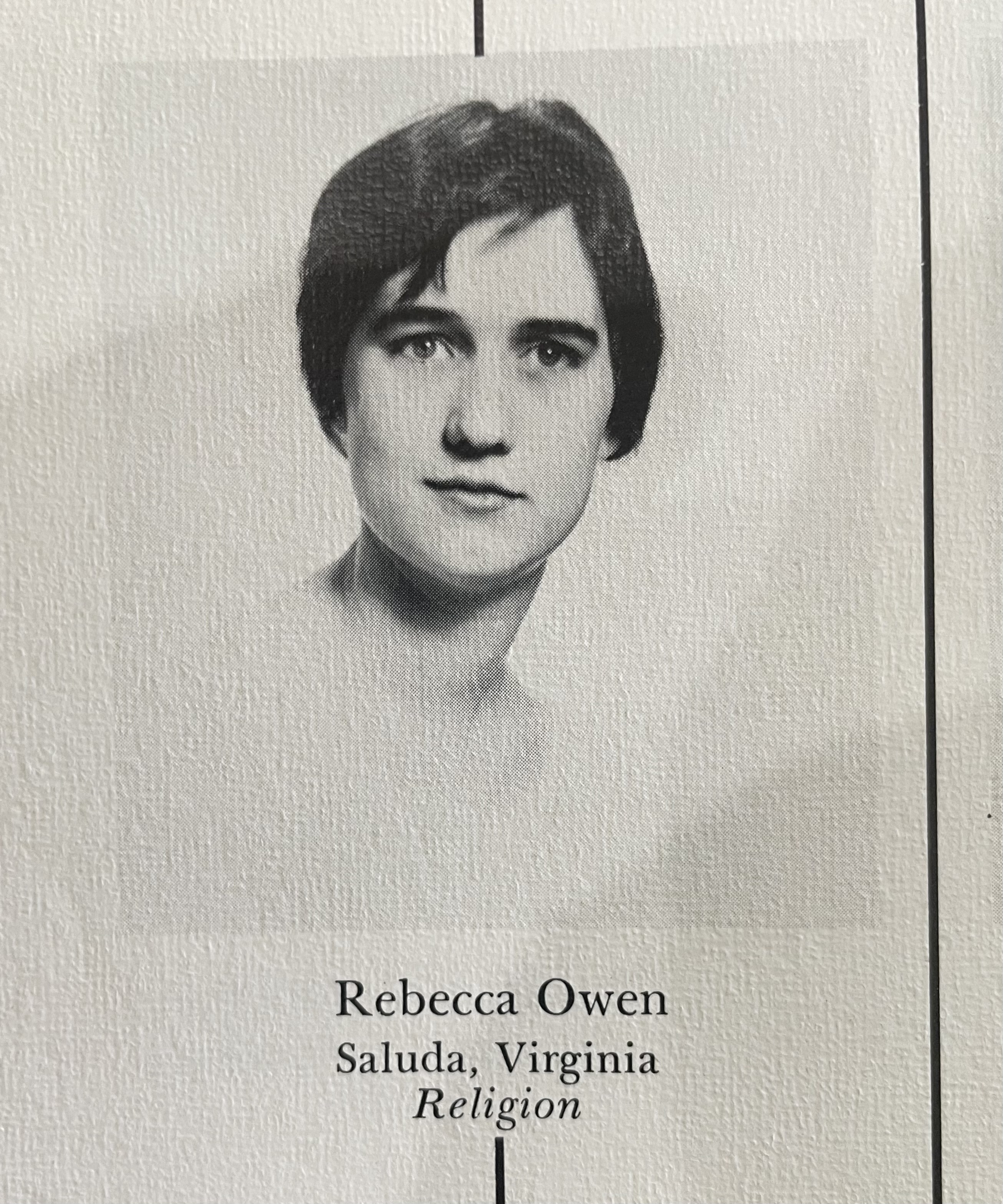

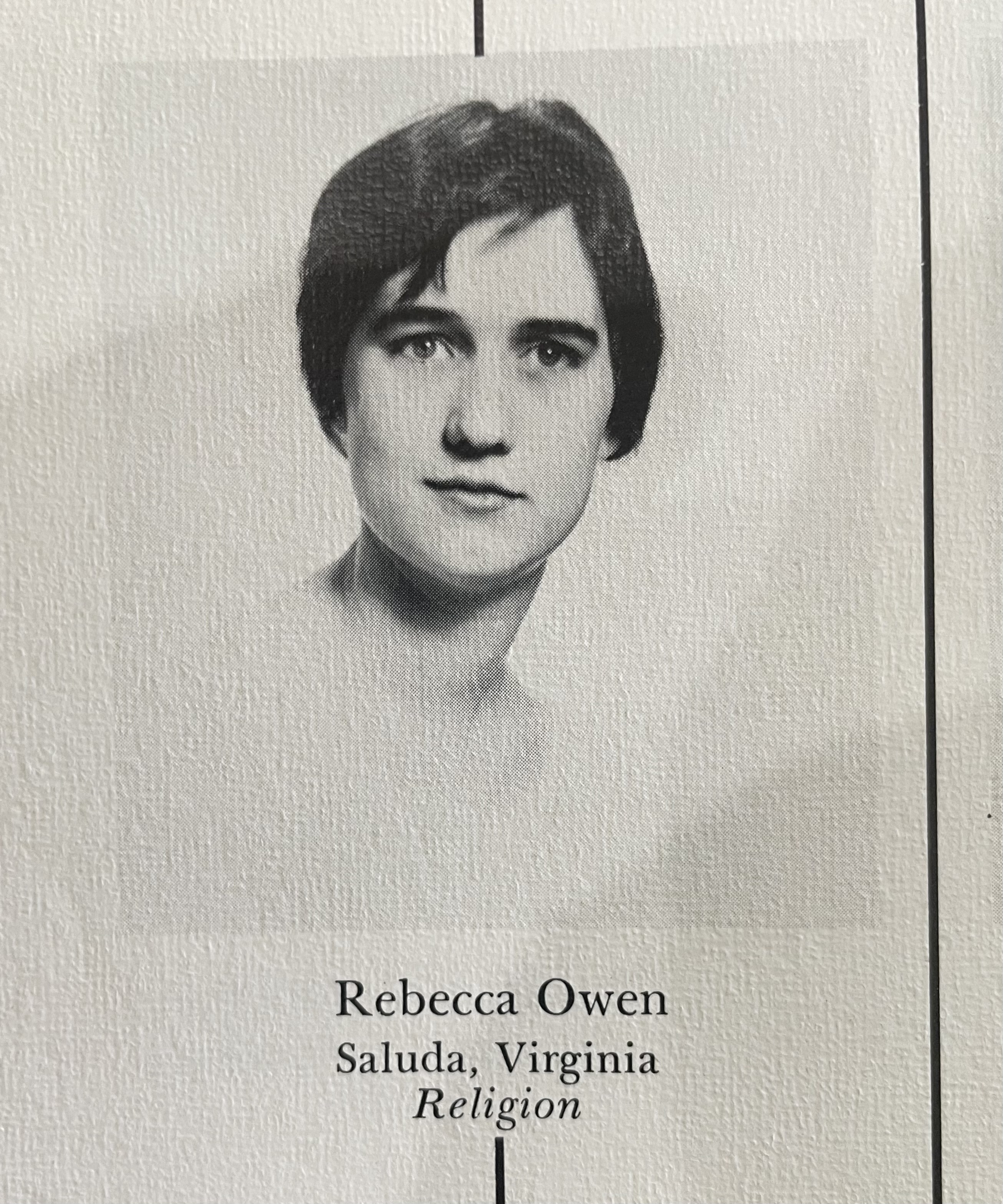

I first heard about Randolph-Macon Woman’s College through a book I read in grad school, Journeys that Opened Up the World by historian Sara Evans. The book is a series of memoirs by sixteen women who were involved in the Student Christian Movement who later became activists in the civil rights movement, anti-war campaign, and the feminist movement. I found the book personally meaningful because several activists had been part of the United Methodist Church’s young adult service program – the same program that I joined after college (and where I met my spouse). One of the memoirs was written by Rebecca Owen, one of the leaders of the civil rights movement in Lynchburg and a student at Randolph-Macon Woman’s College. I paid special attention to Becky’s memoir in particular because she, like me, had grown up Methodist, became a leader in the denomination, and saw her activism as an outgrowth of her faith.

When I first applied for a job at Randolph, I decided to do my teaching demonstration on the sit-in movement. Though I didn’t talk about Becky Owen or the other members of the Patterson Six, I did reference their story at the end of my demonstration – in part to help make my point that the Civil Rights Movement was a grassroots movement.

After arriving at Randolph, I have continued to be fascinated by Becky’s story, assigning her memoir in my American Women’s History course and searching out any other material I can find on her.

This summer, I finally had the opportunity to sort through some of that research and put together a talk before Randolph’s first-year class (the largest in the college’s 130+ year history). The lecture was a co-lecture with my esteemed colleague, Dr. Amy Cohen of Classics and Theatre, where we wove Becky’s story with that of Antigone, the Greek play for this year.

The lecture went off really well. Though collaboratively creating anything can be more difficult, it can also be more fun – and I think our final product was both creative and compelling.

One story that I discovered while doing the research is that Becky attended a Student Christian Movement conference in the fall of 1960, right before the start of her senior year. She met Black activists who had pioneered the sit-in movement such as Rev. James Lawson, the young minister who taught John Lewis and others how to get in “good trouble.” “The imperative of the Denver conference was unambiguous,” Becky recalled in her memoir. “If you, Becky Owen, are serious about Christianity and injustice, get the hell back to Lynchburg and do something.” Upon returning to R-MWC, Becky reached out to Rev. Virgil Wood, pastor of Diamond Hill Baptist, and with the help of the YWCA they began organizing discussion groups that brought together college students and Black community leaders. A couple months later, six college students who’d been involved in the discussion groups headed to Patterson’s Drug Store in downtown Lynchburg…

If you want to hear the rest of the story, I gave a version of this talk the following Sunday at First Christian Church.

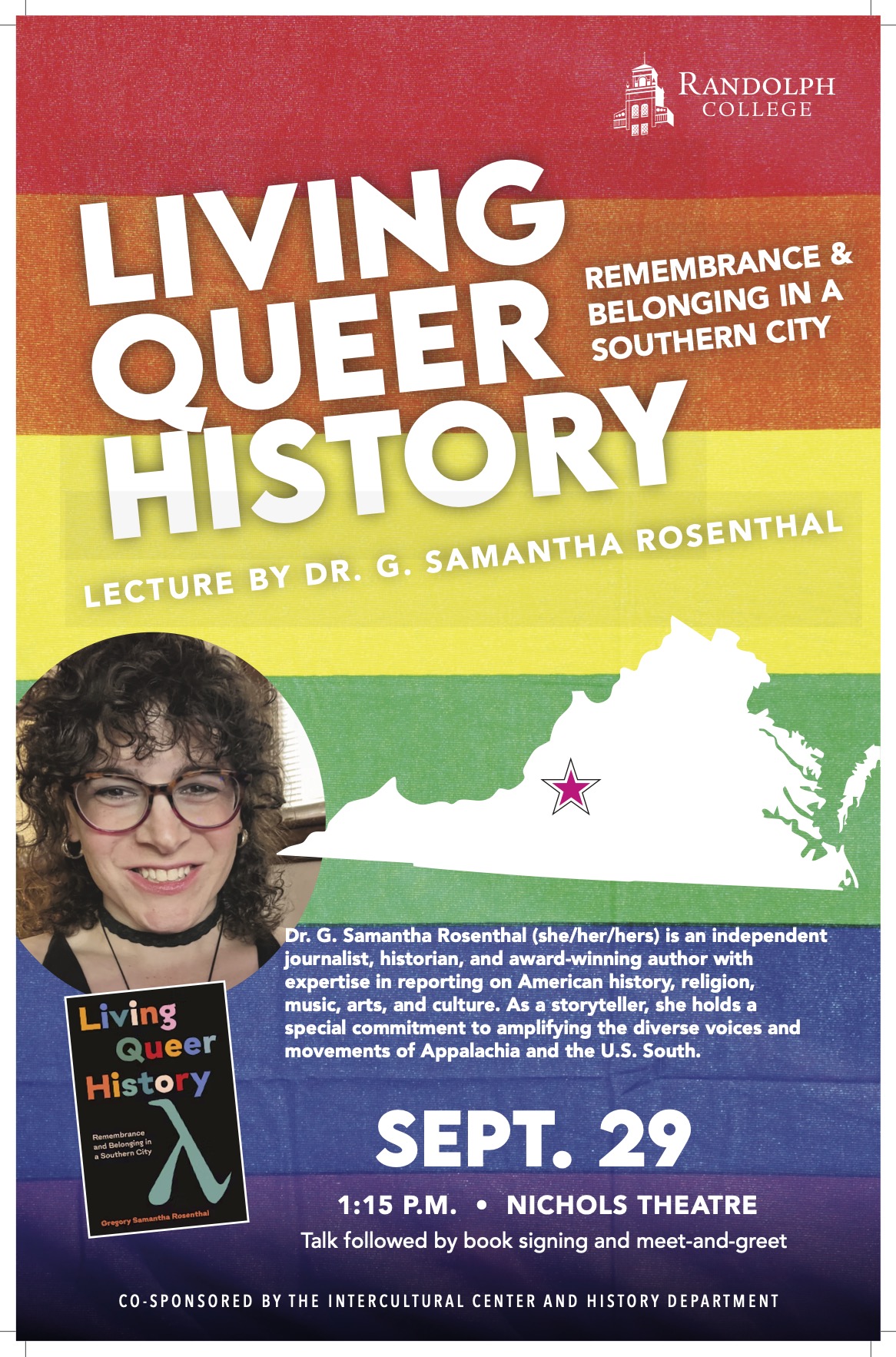

29 Sep 2025

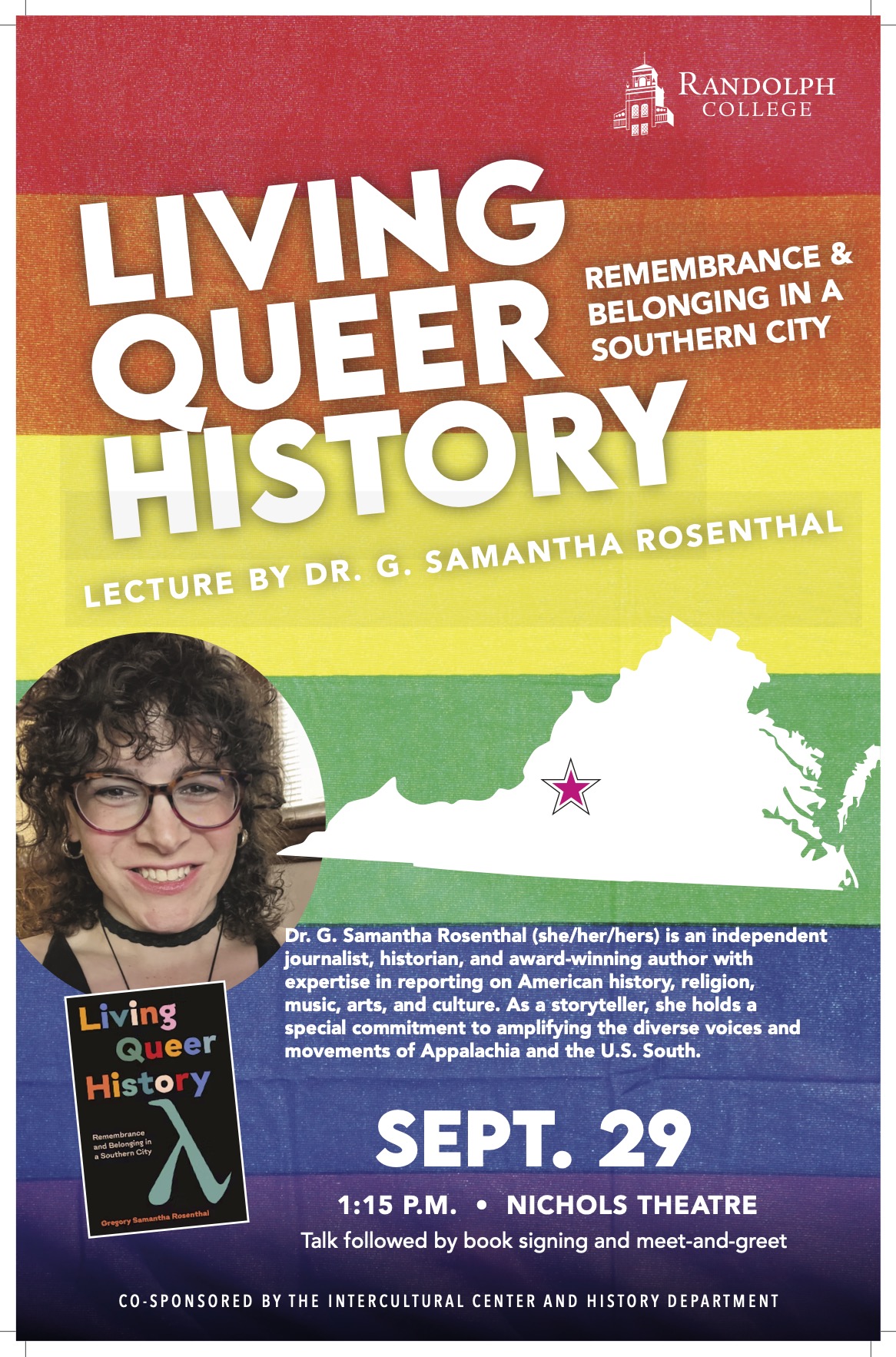

This fall I taught Queer American History. Every student in the class wanted to be there, wanted to do the readings, wanted to talk about what they were learning – it created a pretty magical learning environment!

One of the high points was a guest lecture by Dr. Samantha Rosenthal. With the help of the History Department and the Intercultural Center, I invited Dr. Samantha Rosenthal to join us on campus to talk about her book, Living Queer History: Remembrance and Belonging in a Southern City, published by UNC Press in 2021. The talk was wonderful – several students wrote in their senior capstones that they found it inspirational. Follow her substack if you’re not already!

One of the greatest treats as a teacher is when students decide they want to do their senior capstone on something pertaining to what they learned in your class. This year, two of the seniors in my class told me they’re now planning to write on queer history! One is even using the oral histories and digitized archive created by the Southwest Virginia LGBTQ+ History Project that Dr. Rosenthal helped lead.

Huge thanks to Dr. Rosenthal and to Kathleen, David, and Gail who helped make this course so special!

18 Jul 2025

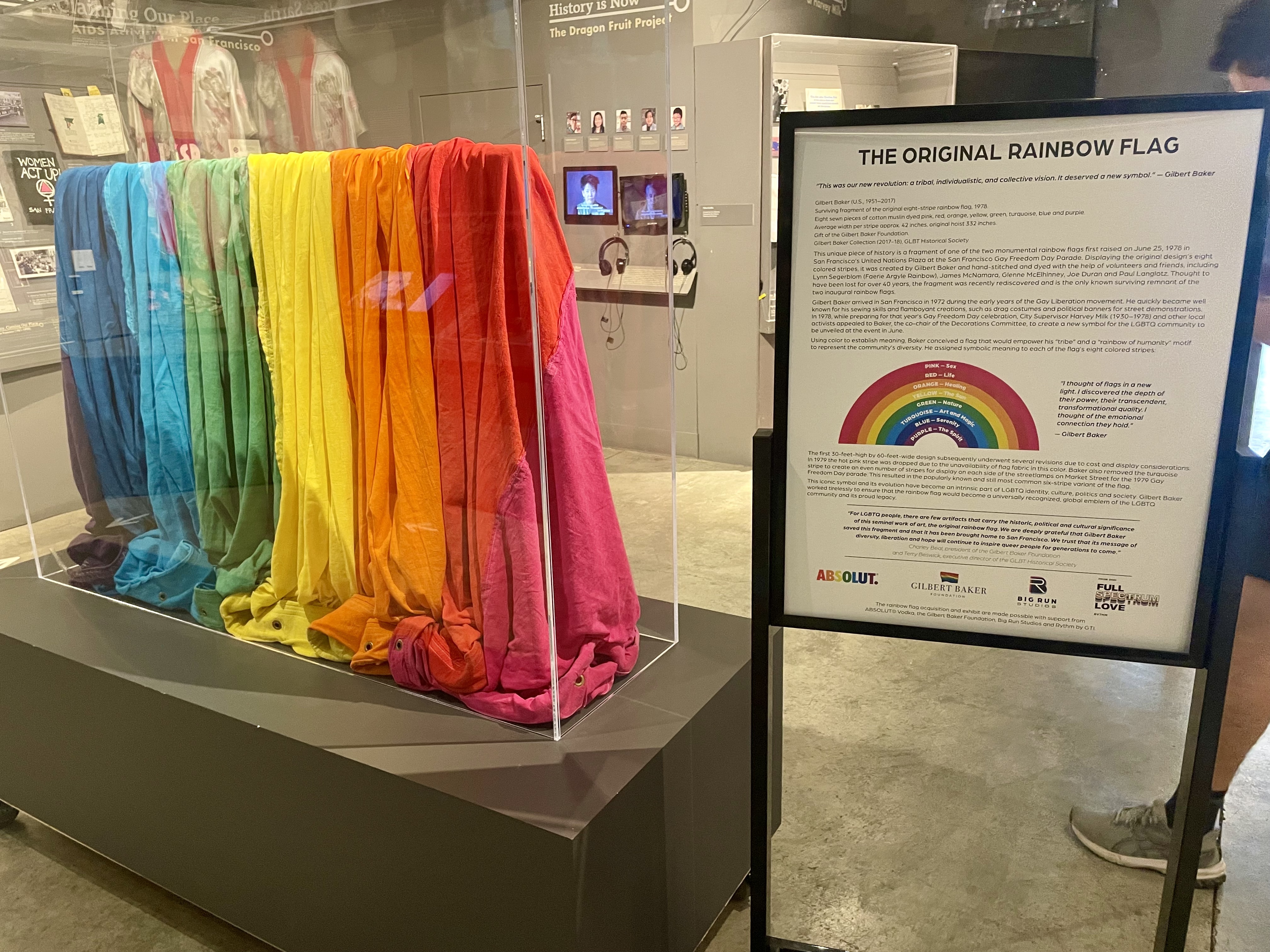

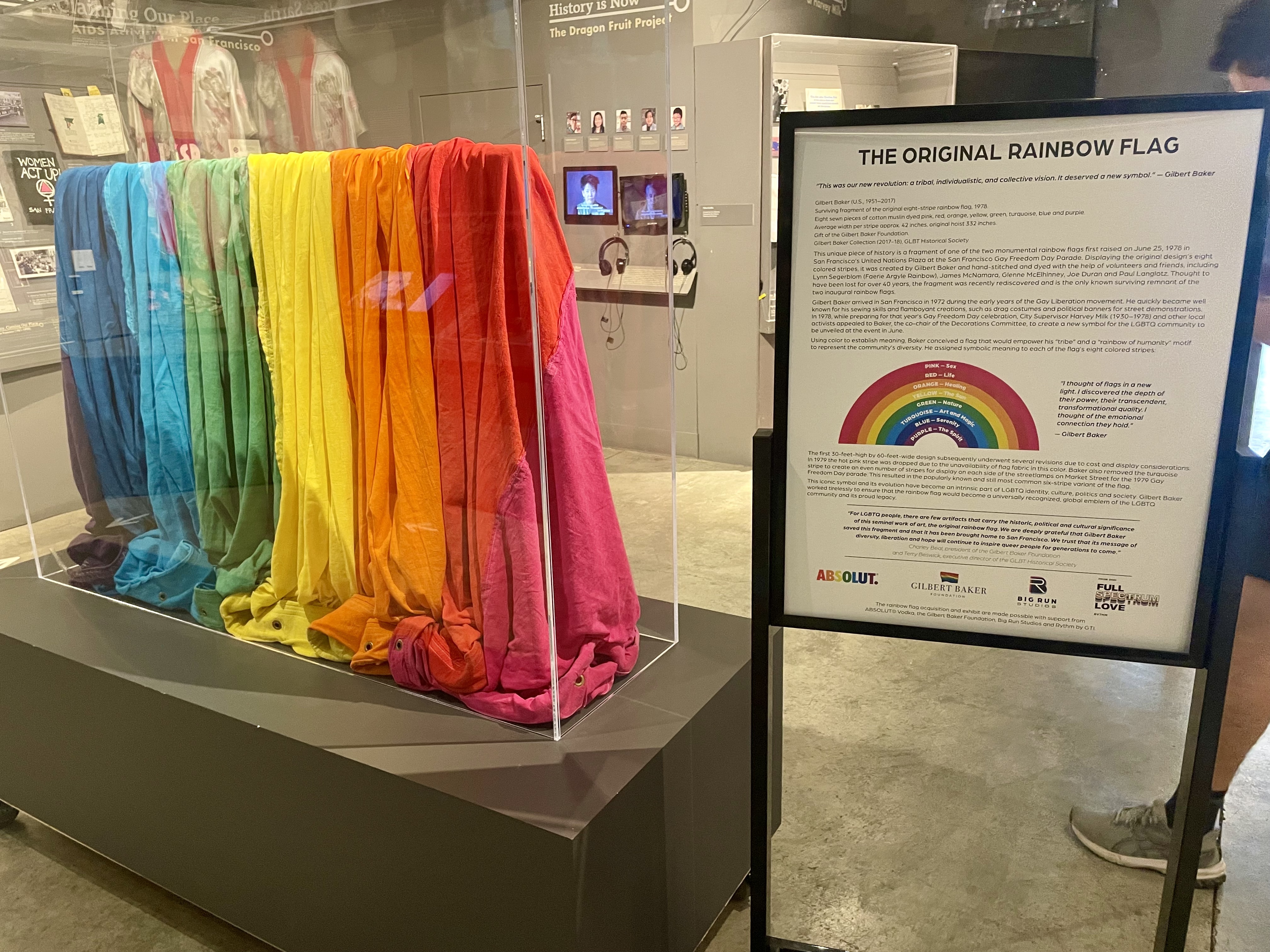

This past year, I received support from the Ruth Borker Fund for Women’s Studies to develop a new course on Queer History at Randolph College. Named in honor of a former Randolph professor, the Borker Fund supports faculty efforts to integrate “gender-related perspectives into the curriculum.”

When I first arrived at Randolph, I didn’t anticipate teaching Queer History. But over the past three years, I’ve become convinced that such a course is essential. While I wasn’t formally trained in queer theory or LGBTQ history, I am a social historian committed to centering the experiences of underrepresented groups. In that spirit, I’ve worked to incorporate LGBTQIA+ stories into all of my classes. The student response has been powerful. Many have described this as a “secret” history—one that resonates deeply with their lives and experiences. The need for this course has only grown more urgent amid the current wave of erasure of LGBTQ+ history.

With support from the Borker Fund, I traveled to San Francisco this summer to visit key historical sites. The first day, I visited the Tenderloin neighborhood to check out the Tenderloin Museum, the former site of Compton’s Cafeteria, and Glide Memorial Church. I also traveled to Golden Gate Park to walk through the National AIDS Memorial Grove. I spent the next day in the Castro. I visited the GLBT Historical Society Museum — the first stand-alone LGBTQ history museum in the US - and joined an LGBTQ+ history walking tour. As part of the tour, I visited the Castro Camera, Harvey Milk Plaza, Pink Triangle Memorial, Castro Theatre, and the Rainbow Honor Walk. On my final day, I ferried over to Angel Island State Park, where I was reminded of Margot Canaday’s work on how the federal government policed sexual identity through immigration policy.

The trip helped me think more intentionally about how to frame particular units and introduced new sources and stories - such as the Compton’s Cafeteria Riot - that I plan to incorporate into the syllabus. I’m really looking forward to teaching the course this fall!

24 Apr 2025

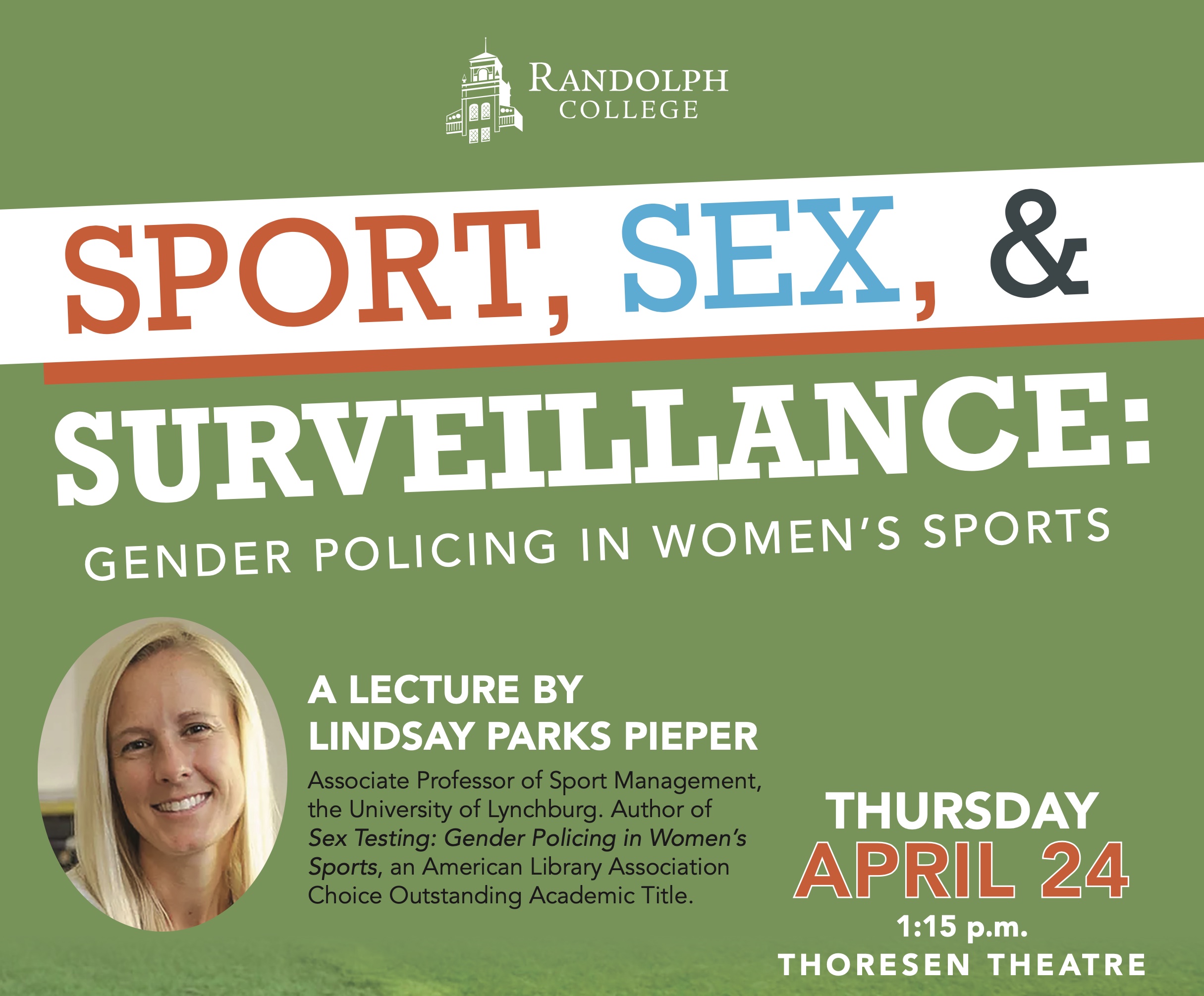

Who gets to play—and who decides?

These two questions are at the heart of ongoing debates about women’s athletics, from the Olympics all the way to college campuses like Randolph.

Fortunately, for those who want to think critically about these questions, we have one of the foremost scholarly authorities right here in Lynchburg.

I was reminded of this last summer while listening to the podcast Tested, produced by the CBC and NPR, in the lead up to the Summer Olympics in Paris. While listening, I heard a familiar voice – that of Dr. Lindsay Parks Pieper.

I found this very exciting because I knew Dr. Pieper personally – we’d met playing pickleball. She’s tall and a former college athlete… so I’ll casually avoid telling you who usually won.

As I listened, I became increasingly convinced that we needed to invite Dr. Pieper to campus. I initially invited her to speak with my American Women’s History class, but word spread—and her visit turned into a campus-wide event. In the end, about 75 Wildcats showed up for her talk.

Lindsay Pieper is the Associate Professor of Health Sciences & Human Performance and the Chair of the Sport Management Department at the University of Lynchburg. She graduated with her BA from Virginia Tech and later received her Masters and Doctorate from The Ohio State University.

Her book, Sex Testing: Gender Policing in Women’s Sport, was published by the University of Illinois Press in 2016. It won several awards including the North American Society for Sport Sociology’s Outstanding Book of the Year, the North American Society for Sport History’s Distinguished Title award, and it was listed as an Outstanding Academic Title by the American Library Association.

Her talk, “Sport, Sex, and Surveillance: Gender Policing in Women’s Sports,” was timely, thought-provoking, and a resounding success.

08 May 2024

Check out this great new article about my time leading the American Culture Program.

Co-leading the American Culture Program has been a blast! The program is unique to Randolph College and is a great example of what makes Randolph special – small classes, experiential learning, and focused on ideas that matter.

For the last two years, we explored the intersection of labor, leisure, and music in the US. We traveled across town in Lynchburg, as well as to Charlottesville, DC, Knoxville, the Highlander Folk School, Memphis, and Nashville and met some amazing labor organizers, activists, musicians, politicians, scholars, and more! We several thought-provoking films, read some excellent books and articles, and had many lively conversations. The theme, “Working for the Weekend,” provided us all with the opportunity to reflect on what we want from our lives and how we can help make the world we want to live in. But it was also a lot of fun – I often described the American Culture Program as an opportunity to design my own “nerd vacation.”

Huge shoutout to my wonderful colleague Julio Rodriguez, our logistics expert Luisa Carrera, and to two great cohorts of students. And a massive thanks to the MANY people who we met with and learned from over the last two years.

You can listen to our collaboratively-created “Working for the Weekend” spotify playlist, review our 2024 syllabus, or see some more pics from our travels on our Insta.

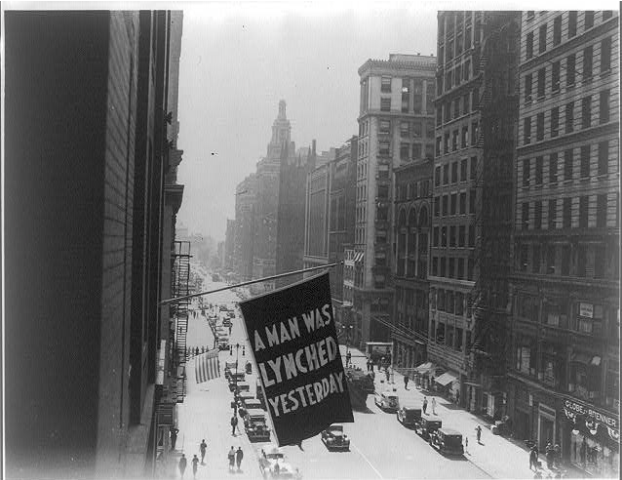

17 Jun 2021

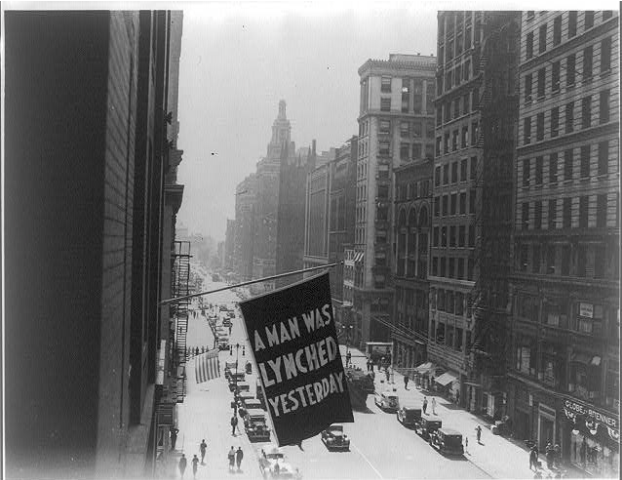

I use images all the time in class. But what about images that could cause harm? Check out my new Hybrid Pedagogy article, “With Care and Context” where I reflect on viewing lynching photographs as an undergraduate and how my thinking about the merits of teaching with such images has evolved over time.

I close my article with a few specific takeaways that I want to include here:

- Ask yourself if showing the potentially harmful image is truly necessary. Does presenting such images prioritize the learning experiences of white students over their classmates of color? Are there ways you can convey similar ideas without showing the image?

- Reflect on how these images fit with the rest of your course. Are most of your discussions of marginalized groups focused on pain and trauma? If so, consider how you might emphasize narratives or images of resistance, resilience, or joy.

- Provide students a chance to opt-out of the in-class viewing. Better yet, due to classroom power dynamics, try framing this as an “opt-in” rather than an “opt-out” experience. Try listing that day as “optional” on the syllabus or consider scheduling a time outside of your regular class session.

- Prepare your students beforehand. Provide ample context for what students will be seeing before presenting the images. Again, this context can frame how your students experience these images and help undermine their dehumanizing potential.

- Clearly state and contextualize the dehumanizing work that the image is doing. Remind students of the personhood of those being represented in the image.

- Maintain a posture of care. Share about your experience viewing the image and acknowledge that the experience of viewing the image will be different for different people. Though it can be harder in larger classes, be sure to check-in with your students before, during, and after the experience. Consider using small groups or “free writes” to provide students a more intimate space to process what they are learning.

- Keep working at it. Giving careful consideration to the images you use in class takes time and persistence, but it’s worth it!

Check out the rest of the article and let me know what you think!

I want to say a big thank you to all the people at Hybrid Pedagogy who made the article better, especially Managing Editor Bethany Thomas and reviewers Brandon Morgan and Daniel Lynds. Thanks for making my first time with a “double-open peer review” process a great one! I also want to say thanks to my wonderful friends and colleagues here at UVA who gave me helpful feedback early on in the process: Gillet Rosenblith, Monica Blair, Allison Kelley, and Grace Hale. And finally, a special shoutout for the Scholars’ Lab and especially Brandon Walsh for pointing me toward Hybrid Pedagogy and digital pedagogy in general!

29 Oct 2019

Crossposted to the Scholars’ Lab blog

THE BLOG

This spring each Praxis Fellow will conduct a workshop on some aspect of digital humanities. Because I study the history of twentieth-century American mass media (especially the radio), I have increasingly found myself interested in sound. During the last few weeks, I have read about the possibilities of using digital tools to analyze and present sound. I plan to share some of my findings in a workshop called “An Introduction to Sound and Digital Humanities.”

I have several goals for this workshop. First and foremost, I want to create a learning environment that is welcoming, inclusive, and relevant. Second, I hope to convey why studying sound is important. Recent sound studies scholars such as Jonathan Sterne have critiqued the idea that a culture of seeing replaced a culture of hearing; yet, this idea still lingers inside and outside of the academy. Third, I want to introduce some of the possibilities and limitations of using digital tools to analyze and present sound. I have divided this workshop (and the rest of this blog!) into three parts: Introduction, Analyzing Sound Collections, and Manipulating and Presenting Sounds. This workshop design is still in progress so I’d appreciate any comments or suggestions!

INTRODUCTION

My first priority as a teacher is to help cultivate an inclusive learning environment where all feel comfortable participating. The design of a space affects both how sounds are made and how people feel welcomed. I plan to rearrange the space into a circle if possible. As a teacher, I enjoy playing music related to the day’s content as students enter my classroom. Music can provide a memorable entry point into a topic. For this workshop, I imagine playing something like Miles Davis’s “Shhh / Peaceful” from his 1969 album In a Silent Way.

I want to begin the workshop with some questions that have a low barrier to entry. For instance, I plan to ask, “What is a sound you love and how does it make you feel?” and “What is a noise you dislike and how does it make you feel?” After giving attendees a chance to think through these questions on their own, I’ll have them share in partners and eventually share with the entire group. By beginning the conversation with reflective questions and a think-pair-share technique, I hope to encourage attendees to feel comfortable contributing verbally. I also hope this introduction will help attendees think about sound in their own lives and the connection between personal and scholarly knowledge about sound. As attendees share their answers, I will guide the conversation to tease out two ideas crucial to sound studies: 1) humans do not just hear with our ears but, as scholar Steph Ceraso has argued, with our whole bodies and 2) how the binary of “sound” and “noise” usually reflects a binary of listening to sounds that are “wanted” or “unwanted.”

ANALYZING SOUND COLLECTIONS

In this section, I hope to encourage attendees to think about the benefits and challenges of using digital tools to analyze sound collections. Much of my thinking here is informed by DH scholar Tanya Clement’s chapter in the edited volume Digital Sound Studies (2018). In this chapter, Clement describes how PennSound scholars thought about the ability of big-data to study large spoken-word audio collections for the NEH-funded High Performance Sound Technologies for Access and Scholarship (HiPSTAS) project. Incorporating Adaptive Recognition with Layered Optimization (ARLO) software used to identify bird sounds, scholars working on HiPSTAS developed a standardized classification system to tag digital audio media so that it could be more searchable. However, as Clement notes, scholars soon came to realize that while classification systems were necessary, they were also limiting. Not everyone agreed on how particular sounds should be classified. Ultimately, Clement proposes that political and historical contexts are embedded in standardized classification systems thereby turning up the volume on how some sounds are heard while turning down the volume on alternate interpretations.

I plan to begin this section by reflecting on how sound files present challenges for scholars because they usually have to be listened to in time. For instance, I will describe how a well-prepared student may have recorded a lecture (ideally with permission!), but the student looking for a key detail from that lecture may still be required to listen to the entire fifty-minute clip just to find the desired detail. The longer the recording, the less inclined a busy researcher is to want to listen. Thus, while sound collections may have tens of thousands of hours of sound files, many of these sounds remain unheard. Thankfully, scholars have utilized machine learning to help organize sound files and make them more accessible to researchers.

I will then introduce an activity that helps students understand how this process of using machines to classify sounds works. I will start by playing three brief sound clips and asking attendees to identify five key words they would use to identify each sound clip. Though I have not finalized which audio pieces I plan to use, I usually try to incorporate material that will seem relevant for my audience. I am currently planning to use a mix of clips that draw on local history and recent popular culture. For instance, I am currently thinking about including a snippet from the 1970 anti-war protest at UVA, a soundbite from an oral history by a UVA women’s history professor, and a brief clip from Spike Jonze’s 2013 film Her.

After attendees have created their five key words for each audio clip, I will give them time to share their results with a partner. Did they come up with the same key words? Different key words? Why or why not? I plan to reconvene the entire group to solicit feedback about the experience. What did they think about the sound clips? How did their key words compare with their partners? For those that had different key words, why might this hinder searchability? How could we improve this process so as to limit these differences?

After teasing out that standardizing keywords may help in this process, I hope to play the clips one more time. This time, I will have attendees classify each clip using the tagging schema developed by scholars working with the PennSound poetry collection. I hope this will demonstrate how standardization can help (though not completely solve) the dilemma of scholars selecting different keywords. At the same time, it will also demonstrate how standardized classification systems can sometimes hide as much as they reveal. For instance, the PennSound tagging schema was designed for spoken word poetry. As a historian, I selected clips that will likely invite different questions and categories. What classifications seem less relevant for these clips? What additional questions or classifications would be helpful for the three clips we heard? Finally, what sounds from these clips might be helpful for a computer to learn to recognize in other clips?

MANIPULATING AND PRESENTING SOUNDS

Analyzing sound collections is only one aspect of how digital humanities can augment sound studies. As time allows (I am envisioning the final 10-15 minutes, but if short on time this section could be cut), I hope to conclude by gesturing toward how digital tools can also allow us to manipulate and present sound. For instance, I plan to mention how attendees can use editing platforms such as the free and open source platform Audacity to create and edit sound files. I hope to ask attendees how manipulating the three sound clips we heard might promote new insights (possible ways I’ve thought about this include editing the lengthy oral history to make it more accessible to the public, adding music to dramatize the Antiwar protest clip, or manipulating Scarlet Johansson’s pitch in the clip from Her to stimulate conversations about pitch’s role in performing and hearing gender and sexuality). In this final conversation, I hope to convey how using audio technologies to manipulate sounds can be beneficial but also has limitations (see for instance Tina Tallon’s article on how audio technologies have distorted higher-pitched voices or how deceptive editing of interviews shaped public perceptions of planned parenthood in 2015).

I plan to conclude my workshop by making a few final remarks using Wendy Hsu and Jonathan Zorn’s Paperphone. In this wrap-up, I will thank attendees, subtly remind them of some key takeaways, and invite them to play with Paperphone tool after the workshop has ended.