10 Oct 2025

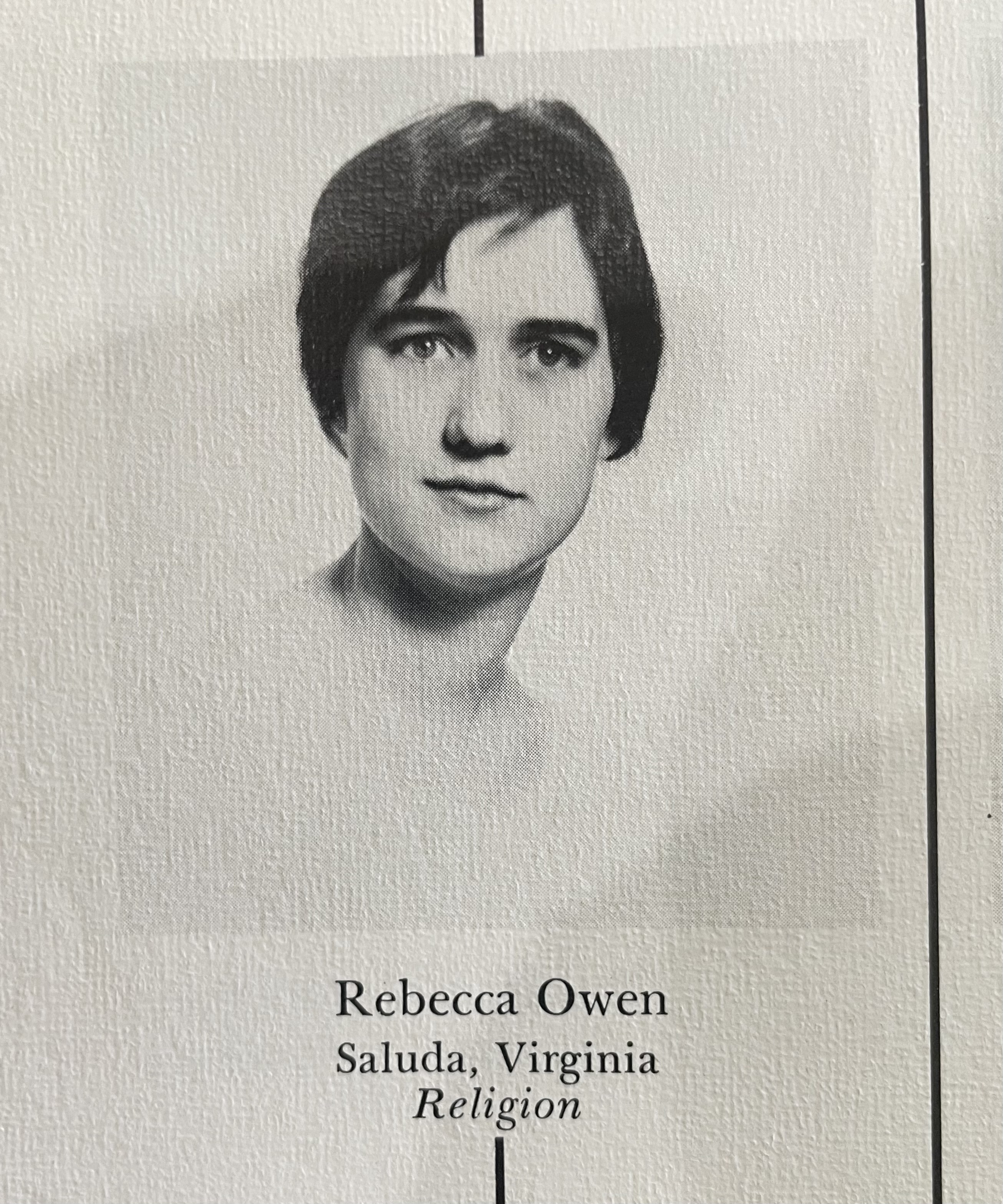

I first heard about Randolph-Macon Woman’s College through a book I read in grad school, Journeys that Opened Up the World by historian Sara Evans. The book is a series of memoirs by sixteen women who were involved in the Student Christian Movement who later became activists in the civil rights movement, anti-war campaign, and the feminist movement. I found the book personally meaningful because several activists had been part of the United Methodist Church’s young adult service program – the same program that I joined after college (and where I met my spouse). One of the memoirs was written by Rebecca Owen, one of the leaders of the civil rights movement in Lynchburg and a student at Randolph-Macon Woman’s College. I paid special attention to Becky’s memoir in particular because she, like me, had grown up Methodist, became a leader in the denomination, and saw her activism as an outgrowth of her faith.

When I first applied for a job at Randolph, I decided to do my teaching demonstration on the sit-in movement. Though I didn’t talk about Becky Owen or the other members of the Patterson Six, I did reference their story at the end of my demonstration – in part to help make my point that the Civil Rights Movement was a grassroots movement.

After arriving at Randolph, I have continued to be fascinated by Becky’s story, assigning her memoir in my American Women’s History course and searching out any other material I can find on her.

This summer, I finally had the opportunity to sort through some of that research and put together a talk before Randolph’s first-year class (the largest in the college’s 130+ year history). The lecture was a co-lecture with my esteemed colleague, Dr. Amy Cohen of Classics and Theatre, where we wove Becky’s story with that of Antigone, the Greek play for this year.

The lecture went off really well. Though collaboratively creating anything can be more difficult, it can also be more fun – and I think our final product was both creative and compelling.

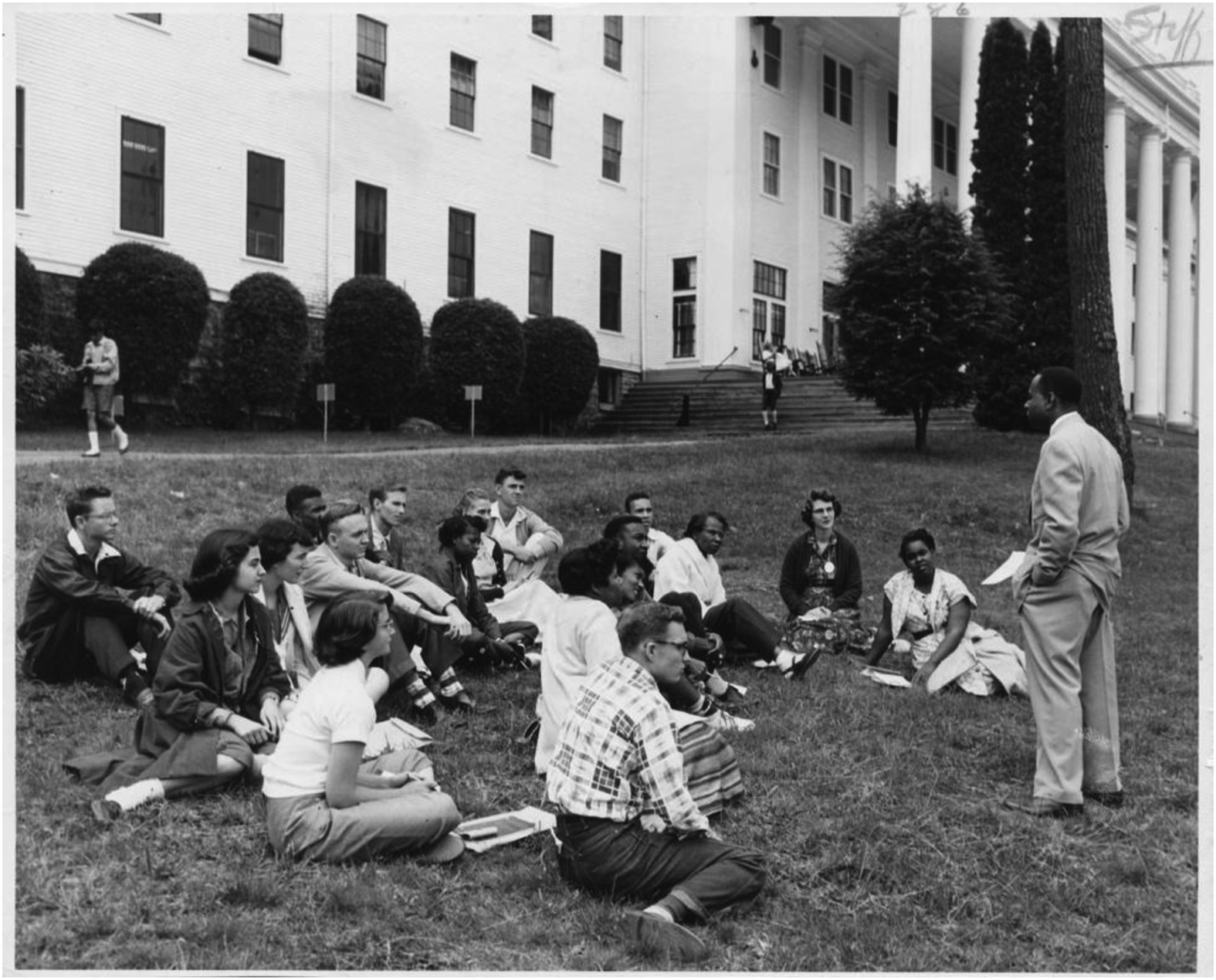

One story that I discovered while doing the research is that Becky attended a Student Christian Movement conference in the fall of 1960, right before the start of her senior year. She met Black activists who had pioneered the sit-in movement such as Rev. James Lawson, the young minister who taught John Lewis and others how to get in “good trouble.” “The imperative of the Denver conference was unambiguous,” Becky recalled in her memoir. “If you, Becky Owen, are serious about Christianity and injustice, get the hell back to Lynchburg and do something.” Upon returning to R-MWC, Becky reached out to Rev. Virgil Wood, pastor of Diamond Hill Baptist, and with the help of the YWCA they began organizing discussion groups that brought together college students and Black community leaders. A couple months later, six college students who’d been involved in the discussion groups headed to Patterson’s Drug Store in downtown Lynchburg…

If you want to hear the rest of the story, I gave a version of this talk the following Sunday at First Christian Church.

15 May 2025

This year, I was honored to be selected for the Quillian International Scholar Study Abroad Seminar in Sri Lanka.

Last year, Randolph hosted Sri Lankan scholar Sudesh Mantillake as our Quillian Visiting International Scholar. I was fortunate to get to know Dr. Mantillake over the course of the year – his office was just down the hall from mine—and I was especially impressed by his performance of Kandyan dance in February, an event attended by the Sri Lankan ambassador.

Throughout the spring, the Randolph delegation followed a rigorous preparation schedule. We attended weekly information sessions on Sri Lankan history, religion, culture, and food, and many of us visited the Sri Lankan Embassy in D.C.

I also used this time to begin researching historical connections between the U.S. and Sri Lanka.

The first thing I discovered was that Sudesh was not the first Sri Lankan to perform Kandyan dance at Randolph! The R-MWC newspaper, The Sun Dial, reported that two members of the Ceylon National Dancers performed here in 1962. When I showed the image to Sudesh, he was blown away—the male dancer had been one of his mentors!

That discovery led me to wonder: Had Sri Lanka played a role in American religious history?

I started by thinking about the 1932 Hocking Report, titled Re-Thinking Missions: A Laymen’s Inquiry After One Hundred Years. I had first encountered it in David Hollinger’s Protestants Abroad, which highlights its pivotal role in reshaping Protestant missions and American Protestantism more broadly.

As a former Global Mission Fellow of the United Methodist Church—here’s my blog and podcast from those years—Hollinger’s arguments made total sense to me. It helped explain why I had such as radically different understanding of “mission” and a “missionary” than did evangelical Christians. In part, it’s because my tradition had been so influenced by the Hocking Report.

I discovered that the Laymen’s committee did indeed travel to Ceylon as part of their research. However, I wasn’t able to find any digitized sources detailing their time there. Ah the joys and challenges of doing social history…

A bit more internet digging led me to Howard Thurman as another possible link between American religious history and Sri Lanka.

I had read Thurman’s Jesus and the Disinherited in grad school and knew how deeply it had been shaped by his 1935 journey to India. During that trip, he met with Gandhi and helped forge a spiritual and intellectual link between Gandhian nonviolence and the American civil rights movement.

I also knew that his papers had been digitized through Boston University’s Howard Thurman Papers Project.

What I quickly discovered was that Thurman didn’t just travel to India—he also spent time in Ceylon (Sri Lanka) and Burma (Myanmar).

As I dug into his journal from his time in Ceylon, I began to see that Sri Lanka played a far more crucial role in shaping his ideas than I had realized.

I presented a paper on this research titled “Transformative Travel: Howard Thurman’s Pilgrimage to Ceylon and the Making of the U.S. Civil Rights Movement.”

Since I don’t anticipate publishing this research formally, I’m sharing the presentation text here.

27 May 2022

This spring, I successfully defended my dissertation and graduated from the University of Virginia with my PhD. I’m now Dr. Connor S. Kenaston!! I also accepted a job at Randolph College where I’ll be the Ainsworth Visiting Assistant Professor of American Culture. More on that later! For now, I want to publicly thank those who helped me get to this point:

Dissertation Acknowledgements

I wrote this dissertation with the advice, support, friendship, and love of so many people. Those mentioned below are just the beginning. I have inevitably omitted many folks who should be included. Thankfully, they’re good people so I’m confident they’ll forgive my oversight. As with the rest of this dissertation, all mistakes are my own.

I want to begin by thanking my advisor, Grace Hale. Grace exemplifies what it means to be an excellent teacher and scholar. Through countless conversations and line-edited drafts, she challenged me to refine my ideas and write more clearly. She paired these high expectations with an endless stream of kindness, encouragement, and laughter. Grace showed me with her words and deeds that she cared about me as both a scholar and a person. I am truly grateful to have had her as an advisor these past six years. I also want to thank Claudrena Harold, Matthew Hedstrom, Kathryn Lofton, and Sarah Milov. I have learned from each of these brilliant scholars over the years, and it was an honor to have them serve on my dissertation committee. They gave me smart and generous feedback, and I know that the next iteration of this project will be all the better for it.

This dissertation was financially supported by the American Historical Association, American Jewish Historical Society, American Society of Church History, Friends of the University of Wisconsin-Madison Libraries, Jacob Rader Marcus Center of the American Jewish Archives, Presbyterian Historical Society, Renate Voris Fellowship Foundation, and Rockefeller Archive Center. I also received support from several UVA institutions including the Americas Center / Centro de las Américas, Department of History, Graduate School of Arts and Sciences, Scholars’ Lab, and Society of Fellows. Thank you to these organizations for making my research possible.

Several colleagues provided me with essential feedback on my work. Monica Blair, Allison Kelley, Kevin Rose, and Gillet Rosenblith were absolutely integral to this project. I greatly benefitted from their friendship and wisdom. Friends from the history department who provided me with helpful feedback include Cleo Boyd, Jon Cohen, Crystal Luo, Olivia Paschal, and Joey Thompson. Brittany Acors, Bradley Kime, Melanie Pace, Maxwell Pingeon, and other members of the Virginia Colloquium of American Religion also gave me helpful advice at various stages of this project; special thanks to Isaac May for essential and timely feedback on two of my chapters. I benefitted tremendously from participating in an interdisciplinary writing group with Sarah Winstein-Hibbs, Erin Jordan, and Kelvin Parnell. Their keen insights helped me to think broadly about my topic and provided me the structure I needed during a pivotal stage of my writing. I also received helpful feedback from participants at conferences including the U.S. Religious Studies and New Histories of Capitalism conference and the annual meetings of the American Studies Association, Organization of American Historians, and American Society of Church History.

I greatly appreciated the opportunity to discuss my scholarship with David Catchpole, Eden Consenstein, Kati Curts, Philip Goff, Lerone Martin, Bethany Moreton, Suzanne Smith, and David Walker. I am grateful for my undergraduate faculty mentors, Crystal Feimster and Glenda Gilmore, who taught me that I belonged at Yale and encouraged me to embark on this graduate school journey. Thanks to Kathleen Miller, Pamela Pack, Kelly Robeson, and Jennifer Via for the work they have done to make the History department run smoothly. Thanks also to Brian Balogh, Fahad Bishara, Kevin Gaines, Jack Hamilton, James Loeffler, Andrew Kahrl, Kyrill Kunakhovich, Kai Parker, Heather Warren, and Penny Von Eschen for their support. Thanks as well to the many archivists, librarians, and others who helped me find the materials I needed. Special thanks to Michelle Levy, Mary Pratt, Brandon Butler, and Susan Ferland.

I also want to thank the family and friends who hosted me during my travels. Bob Boyce and Tom Cytron-Hysom made me feel like one of the family during my time in Minneapolis and Saint Paul. Staying with Gavan Gideon for a few days when he was back in Minnesota also warmed my soul during frigid January days. Krisha Desai graciously let me use her apartment while in Philadelphia. Though they knew me only as a “friend of a friend,” Robert and Sarah Emerson agreed to host me for several weeks in Madison, Wisconsin, and we became fast friends! Fiona Vella, Chelsea Spyres, and Ryan Palmer hosted me and provided me with transportation for various mid-Atlantic archival trips. Daniel Gordan, Lea Winter, and Rachel Kenaston hosted me during trips to New York City while my uncles, Tom Kenaston and James Adolf, treated me to several laughter-filled meals. Willis Jenkins and Rebekah Menning generously allowed me to use their cabin for writing retreats.

I’d also like to thank my digital and public humanities communities for helping me to imagine and live into a new, kinder academy. Special thanks to my Praxis Fellowship friends Janet Dunkelbarger, Natasha Roth-Rowland, Lauren Van Next, and Chloe Downe Wells. I am exceedingly grateful to have had Brandon Walsh as a mentor and friend for the last few years. I am also thankful for other staff at the Scholars’ Lab, especially Jeremy Boggs, Ronda Grizzle, Shane Lin, Drew Macqueen, Laura Miller, Ammon Shepherd, and Amanda Visconti. I have appreciated the opportunity to work this past year with the brilliant staff at the Jefferson School African American Heritage Center including Andrea Douglas, Sherry Bryant, Leslie M. Scott-Jones, and Jordy Yager.

I also need to say a big thank you to my union, United Campus Workers Virginia. UCWVA gave me dignity and purpose during my last few years in graduate school. I’d especially like to thank Gary Broderick and my fellow workers on the statewide UCWVA steering committee: Evan Brown, Crystal Luo, Rosa Hamilton, Ida Hoequist, Kelsey Huelsman, Matthew Conover, Cecelia Parks, Jon Rajkovich, Stephen Marrone, Rose Szabo, Kristin Reed, Waleed Sami, and Mark Wood. Thanks as well to Jess, Carmen, Laura, and Daniel. Solidarity forever!

Loved ones affiliated with the Charis community nourished my soul when I needed it most: Anna Markowitz, Eric Martin, Lindsey, Jordan, Ruby, and Hazel Leahy, Lindsay and Brittany Caine-Conley, Grace Aheron, Rowan Hollins, Claire Hitchins, Julio Quispe, Rebekah Menning, Willis Jenkins, Karl-Jon Sparrman, Martha Morris, Owen Brennan, Christine Hitchins, Laura and Steve Brown, Mark Heisey, and Leah Ruth. The UVA Wesley Foundation positively shaped my experience in Charlottesville. Special thanks to Deborah Lewis, Woody Sherman, Sheila Rush, Justice Eliz, Madi Alvis, Asa and Lauren Nichols, Claire Corkish, and Mary Elder. I also want to thank the wonderful community at Trinity Episcopal Church. I especially want to express my appreciation for Jim and Cathy Loman, Cass and Tish Bailey and family, Leila Brown, Leah Puryear, Barbara Yager, Bethany Gordon, Melissa Moore, Colleen Fennessey, Mark Bell, John Edwin Mason, Patricia Jones-Turner, the Fadils, Ikefunas, Duncans, Stoltzes, Kevin and Jackie Rose, Kristen and Joe Szakos, Elizabeth Cobb, Blair Wilner, Abby and Kyle Nicholas, Helen Plaisance, and Cleve Packer. Thanks as well to Neal Halvorson-Taylor, Maria Chavalan Sut, and Isaac Collins.

Chelsea Spyres, Fiona Vella, Mike DiScala, and Dan Gordan never failed to check in on me and to raise my spirits. Kaitlin Scott filled our home with joie de vivre in the midst of a depressing pandemic. Matthew Paysour and Alli Burks gave us needed laughter, songs, and puppy playtime. Hikes and gatherings with our quarantine family, Matt and Jenny Kragie, have truly been a source of deep joy and love. Good times with Earl, Lee, and Fernanda Vallery and Fran Rinaldo helped fill both hearts and bellies. Other supportive friends from Bowerbird Bakeshop include Mariah Wesley, Kevin Simmons, Drew Reynolds, and the Cincinnatis.

I am grateful for the friendship of UVA history graduate students including Isabel Bielat, Clayton Butler, Daniele Celano, Vivien Chang, Malcolm Cammeron, Ari Cohen, Erik Erlandson, Amy Fedeski, Jack Furniss, Alice King, Shira Lurie, Josh Morrison, Brian Neumann, Laura Ornée, Abeer Saha, Jacqui Sahagian, Nicole Schroeder, Daniel Sunshine, Christopher Whitehead, Justin Winokur, and Kevin Woram. I have appreciated those that have cheered me on from a distance such as Lucas, Owen, and Elisa Endicott, David, Emily, Mark, and Amy Sinclair, Tiffania Willets, Jun Luke Foster, Josh Rubin, Chris Zheng, Jeff Zhang, Adam Sperber, F. Willis and Kristina Johnson, Marcharkelti McKenzie, the Smoots, Ceewin Louder, Katy Wrona, Sarah Roemer, Gretchen Brown, J.F. Lacaria, Julia Hosch, Jarred Phillips, Julie Qiu, Emmalee Fishburn, Zane and Maggie Foster, Eduardo Bousson, Tara and David Hartsfield, Brandon, Katherine, Billy, Diane, and Jamamaw Collins, Kathy and Malcolm Chaney, Susan March, Sarah Cato, Betsy and Alex Canterbury, Ira Slomski-Pritz, Shuaib Raza, Andre Morales, Matt and Lori Brooks, the Bickertons, Groves, Lyghts, Cramers, Claire Daviss, Clare Kane, Nicole Ivey, Zaina Zayyad, Tiffany Bell, Barbara Lutz, the Smiths, Krimmels, Schmidts, Seeleys, Scotts, and so many more wonderful people.

During my second year of graduate school, I gained an entirely new set of family members! My in-laws were loving and supportive throughout this long PhD process. Special thanks to Joe Niechwiadowicz, Kristi and Mark Reierson, Kaitlyn and Mark Niechwiadowicz, and Peter Niechwiadowicz. Thanks as well to Tom and Kathrine Schnabel, Kelli and Zach Robinson, Katie and Nich Pape, Michelle Niechwiadowicz, and Lou Tendeiro. Finally, I would be remiss if I failed to mention my love and appreciation for a host of other Sortebergs, Eidnesses, Kulzers, Merkleys, and Niechwiadowiczes.

I am forever grateful to be so deeply loved by my parents, Joe and Judi Kenaston, and my sisters, Rachel and Diane Kenaston, since my first breath. They have been unbelievably supportive throughout this process and even pitched in as last-minute proof-readers! I am also incredibly thankful to love and be loved by my brother-in-law Adam and three-year-old nephew Isaac. Adam has been a fountain of wisdom for navigating academia while Isaac has been an essential source of delight and giggles in the midst of a sometimes-grueling process. I have always felt loved and supported by my Nana and Grandaddy, Karen Kenaston, Skip French, Tom Kenaston, James Adolf, Barbara, Gary, and Carol Good, Nate and Laura Kennedy, Shauna and Josh Riggs, Chris, Joan, and Robert Prasse, Jane Modlin, Andrew Potter, Joanne Farley, Patricia Ployd, Bob and Jill Modlin, and so many other Modlins! I also want to thank those who have gone before, especially Glenn and Sally Kenaston, Trey Prasse, and John Farley. Finally, the last few months of completing the dissertation was lightened by the newest—and furriest—member of our family, Franklin. Franklin’s dogged persistence that there was more to life than my computer was a life-lesson that I needed and will continue to try to live.

Most of all, I want to thank Maria Niechwiadowicz. Even when times are hard, life with you is so, so good. You spread community, compassion, and joy wherever you go, and I am eternally grateful to have you as my companion on this adventure. Thank you for all the shared hikes, coffee, meals, conversations, pastries, mysteries, laughs, smiles, jokes, walks, travels, tears, friends, blessings, songs, poems, prayers, sunrises, and sunsets. I could write three more dissertations about how your love and support helped get me to this point. But don’t worry, I won’t! Maria, this dissertation is dedicated to you.

01 Apr 2020

Crossposted to the Scholars’ Lab blog

Before I begin this mostly self-focused blog post, I want to acknowledge that the coronavirus pandemic has affected so many people more than me. My heart goes out to all who are sick, suffering, or have died, and to their friends and families. I want to thank all those responding to the crisis and making sure people’s needs are met. You are appreciated.

I have tried to exercise outside at least once per day the last few weeks. I make sure to stay away from other walkers and runners–many of whom are probably like me and only recently re/discovered how much they love exercising outdoors. Trapped inside while attempting to social-distance makes exercising outside a wonderful breath of fresh air, a brief moment away from the attempt to do remote work amidst the steady stream of anxiety-producing news about the virus.

In the last couple weeks, there have been a number of sidewalk chalk messages along my favorite running route. One of the messages was “be gentle with yourself.” Recently, I have found my mind—and my feet—returning to that piece of advice.

A few weeks ago, our Praxis Team was struggling. The coronavirus pandemic had recently begun escalating rapidly in the United States and institutions like UVa were taking necessary precautions. These changes affected Praxis. We would no longer be able to meet in-person as a team. We would no longer be able to publicly present our findings at an in-person gathering in May. Many of us were struggling to remain focused on remote work. How could we continue doing schoolwork when the world outside seemed to be crumbling? Frankly, what was the point?

Thankfully, our outgoing project manager Chloe recognized how people were feeling. Near the beginning of our first Zoom meeting, Chloe encouraged us to have a short meeting and take the rest of the week off from Praxis. Chloe may not have used the same words as my sidewalk messenger, but she might as well have. Be gentle with yourselves, she seemed to be saying.

The week off was helpful. Though the tragedy and the stress remain present, the shock had at least worn off. When we returned, we needed to figure out how to move forward. What elements of our project did we want to prioritize and what elements should we let go of?

Our first time reconvening after the break was to meet with Barbara Brown Wilson and Alissa Diamond. They are two incredibly smart scholars who have thought a lot about space, Charlottesville, property, and equity. They had agreed to meet with us before the pandemic, and they generously agreed to keep the meeting, now to be held over Zoom. While I was glad they could still meet, I couldn’t help but wonder—how helpful will this meeting be considering our new circumstances? Would it be better to get our own ducks-in-a-row first?

To my surprise, the meeting was exactly what we needed. Our guests gave us some excellent feedback about our project. Alissa Diamond even generously offered to share some of her findings from the UVa Library’s now-closed Special Collections. I was especially appreciative of Barbara Brown Wilson’s words that all good scholars have to constantly adjust the scope of their projects. Narrowing the scope of our project was not a sign of failure. Again, the sidewalk messenger seemed to call out, “be gentle with yourself.”

I am unsure of what the next six weeks will look like. As a Praxis Team, we still want to accomplish a version of what we set out to create. We know our project likely won’t look the same as what we dreamed of creating a few months ago. But we are resolved to be ok with that. As the first bullet point in the Charter we created last fall reminds us, we value “process over outcome.”

Even though yesterday’s rain washed away the chalk, I want to continue returning to my sidewalk message. In this time of tragedy, we could all use with the reminder to be gentle with ourselves and each other.