Below you'll find a collection of Kenaston's past blog posts. You can also use the navigation bar to learn more about Kenaston, his research, and his pedagogy.

15 May 2025

This year, I was honored to be selected for the Quillian International Scholar Study Abroad Seminar in Sri Lanka.

Last year, Randolph hosted Sri Lankan scholar Sudesh Mantillake as our Quillian Visiting International Scholar. I was fortunate to get to know Dr. Mantillake over the course of the year – his office was just down the hall from mine—and I was especially impressed by his performance of Kandyan dance in February, an event attended by the Sri Lankan ambassador.

Throughout the spring, the Randolph delegation followed a rigorous preparation schedule. We attended weekly information sessions on Sri Lankan history, religion, culture, and food, and many of us visited the Sri Lankan Embassy in D.C.

I also used this time to begin researching historical connections between the U.S. and Sri Lanka.

The first thing I discovered was that Sudesh was not the first Sri Lankan to perform Kandyan dance at Randolph! The R-MWC newspaper, The Sun Dial, reported that two members of the Ceylon National Dancers performed here in 1962. When I showed the image to Sudesh, he was blown away—the male dancer had been one of his mentors!

That discovery led me to wonder: Had Sri Lanka played a role in American religious history?

I started by thinking about the 1932 Hocking Report, titled Re-Thinking Missions: A Laymen’s Inquiry After One Hundred Years. I had first encountered it in David Hollinger’s Protestants Abroad, which highlights its pivotal role in reshaping Protestant missions and American Protestantism more broadly.

As a former Global Mission Fellow of the United Methodist Church—here’s my blog and podcast from those years—Hollinger’s arguments made total sense to me. It helped explain why I had such as radically different understanding of “mission” and a “missionary” than did evangelical Christians. In part, it’s because my tradition had been so influenced by the Hocking Report.

I discovered that the Laymen’s committee did indeed travel to Ceylon as part of their research. However, I wasn’t able to find any digitized sources detailing their time there. Ah the joys and challenges of doing social history…

A bit more internet digging led me to Howard Thurman as another possible link between American religious history and Sri Lanka.

I had read Thurman’s Jesus and the Disinherited in grad school and knew how deeply it had been shaped by his 1935 journey to India. During that trip, he met with Gandhi and helped forge a spiritual and intellectual link between Gandhian nonviolence and the American civil rights movement.

I also knew that his papers had been digitized through Boston University’s Howard Thurman Papers Project.

What I quickly discovered was that Thurman didn’t just travel to India—he also spent time in Ceylon (Sri Lanka) and Burma (Myanmar).

As I dug into his journal from his time in Ceylon, I began to see that Sri Lanka played a far more crucial role in shaping his ideas than I had realized.

I presented a paper on this research titled “Transformative Travel: Howard Thurman’s Pilgrimage to Ceylon and the Making of the U.S. Civil Rights Movement.”

Since I don’t anticipate publishing this research formally, I’m sharing the presentation text here.

24 Apr 2025

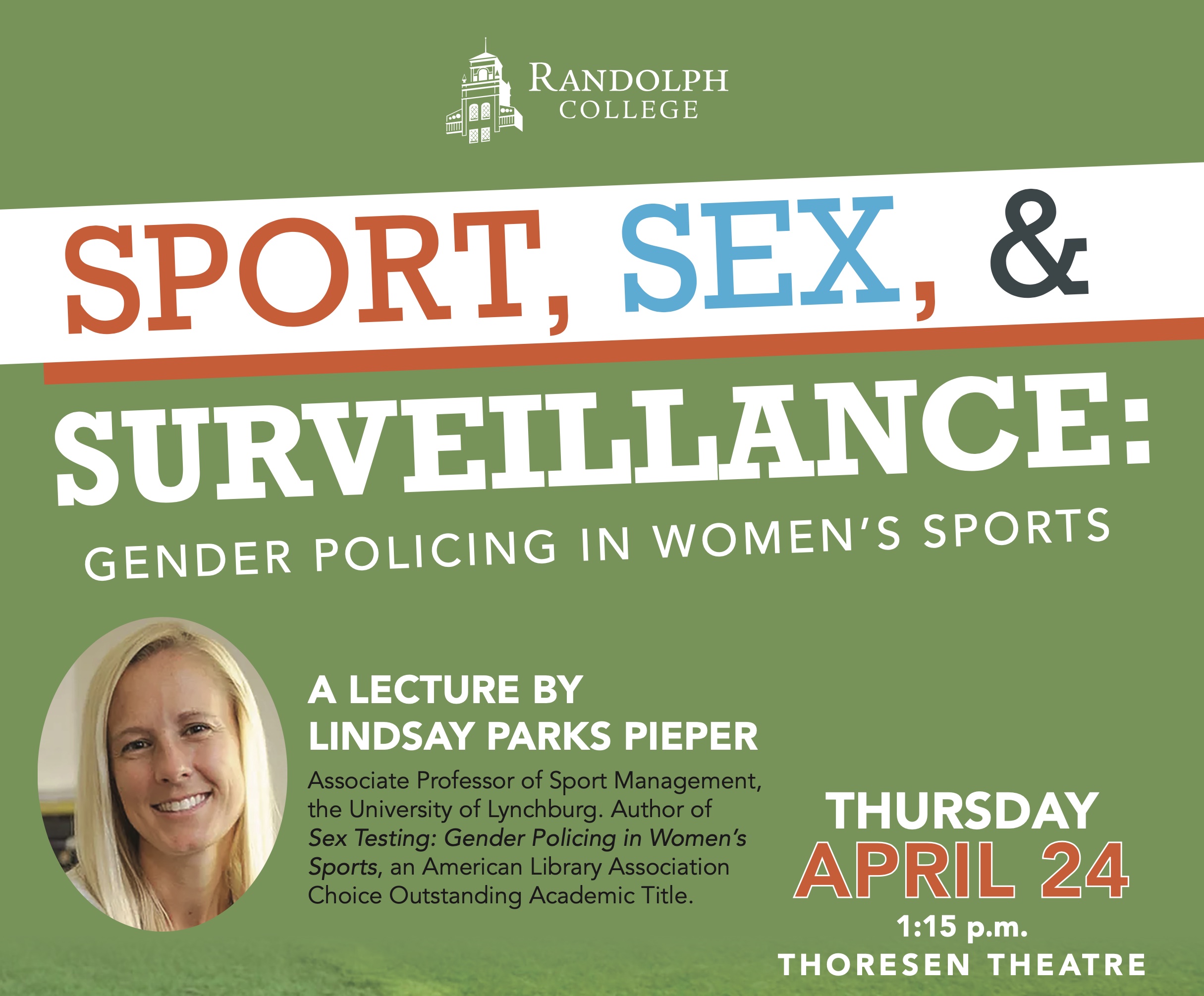

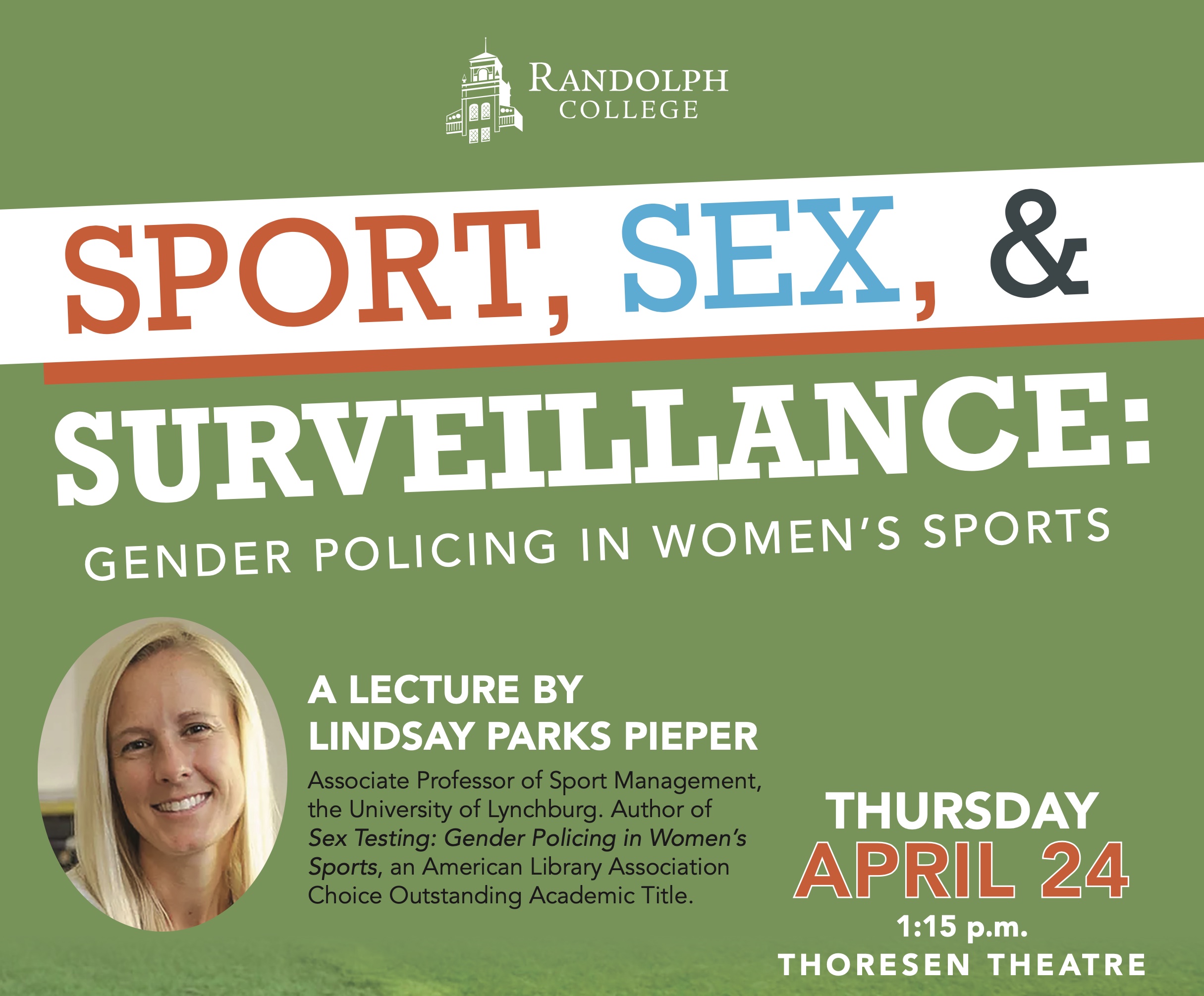

Who gets to play—and who decides?

These two questions are at the heart of ongoing debates about women’s athletics, from the Olympics all the way to college campuses like Randolph.

Fortunately, for those who want to think critically about these questions, we have one of the foremost scholarly authorities right here in Lynchburg.

I was reminded of this last summer while listening to the podcast Tested, produced by the CBC and NPR, in the lead up to the Summer Olympics in Paris. While listening, I heard a familiar voice – that of Dr. Lindsay Parks Pieper.

I found this very exciting because I knew Dr. Pieper personally – we’d met playing pickleball. She’s tall and a former college athlete… so I’ll casually avoid telling you who usually won.

As I listened, I became increasingly convinced that we needed to invite Dr. Pieper to campus. I initially invited her to speak with my American Women’s History class, but word spread—and her visit turned into a campus-wide event. In the end, about 75 Wildcats showed up for her talk.

Lindsay Pieper is the Associate Professor of Health Sciences & Human Performance and the Chair of the Sport Management Department at the University of Lynchburg. She graduated with her BA from Virginia Tech and later received her Masters and Doctorate from The Ohio State University.

Her book, Sex Testing: Gender Policing in Women’s Sport, was published by the University of Illinois Press in 2016. It won several awards including the North American Society for Sport Sociology’s Outstanding Book of the Year, the North American Society for Sport History’s Distinguished Title award, and it was listed as an Outstanding Academic Title by the American Library Association.

Her talk, “Sport, Sex, and Surveillance: Gender Policing in Women’s Sports,” was timely, thought-provoking, and a resounding success.

18 Mar 2025

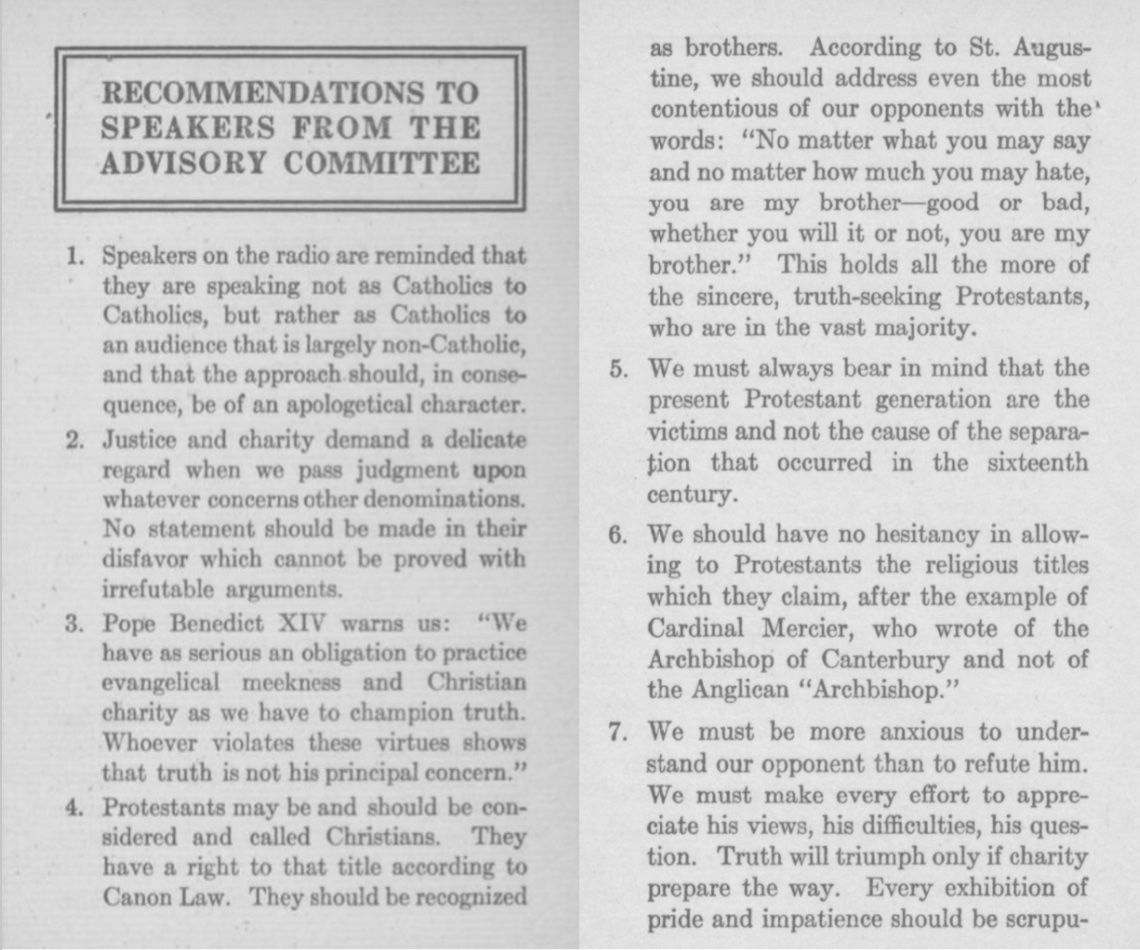

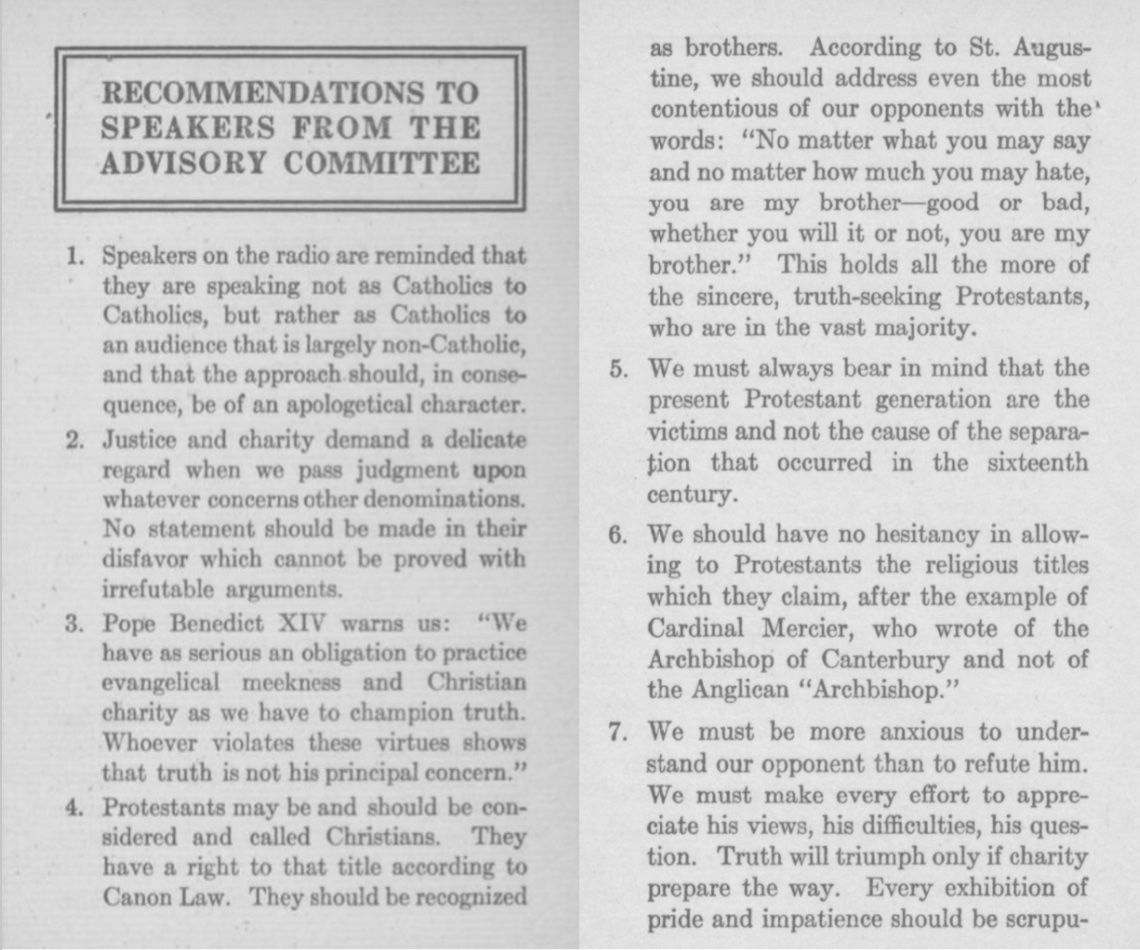

This spring, I headed to New Orleans to present a paper, “Forgotten Frequencies: Network Religious Radio and the Rise of Tri-Faith America.” The paper focused especially on NBC’s The Catholic Hour in the 1930s. The popular program emerged during an era rife with nativism and Protestant nationalism, and it powerfully demonstrated that Catholics could be both fully American and fully Catholic. Yet, to package Catholicism for a mass audience, Catholic organizers had to make strategic compromises that maintained Catholicism’s distinctiveness but didn’t offend non-Catholic listeners. This balancing act, I argued, helped pave the way for for Americans during and after World War II to see Protestants, Catholics, and Jews as co-equal pillars of American religious life.

Here’s a short Randolph News article about my paper: Kenaston Presents at Southeastern American Studies Association Conference.

16 Feb 2025

I was recently invited to give a talk about Methodist history and racial justice to the William and Mary Wesley Foundation. While the first half focused on standard denominational history, the second half I focused in on lessons we can draw from the Student Christian Movement, using my Modern American History article. Overall, the experience was a lot of fun, and I’m thankful to Rev. Ryan LaRock for inviting me!

13 Dec 2024

My review of Dixie Heretic: The Civil Rights Odyssey of Renwick C. Kennedy by the late Tennant McWilliams is in the December 2024 issue of the Journal of American History! The book is a deeply researched biography of white Southern minister Renwick Kennedy and his (often unsuccessful) efforts to change his fellow white Christians’ attitudes about race and poverty.

You can read my review here.

08 Aug 2024

This fall I spearheaded and served as the de facto chair of the nonpartisan #RandolphVotes initiative. Our aim was to boost voter participation and foster civil discourse on campus during the 2024 Presidential election. #RandolphVotes ensured Randolph College fulfilled its obligation under section 487(a)(23) of the Higher Education Act to make a “good faith effort” to distribute voter registration forms to their students.

As part of our initiative, promoted voter registration, organized transportation ot the polls, hosting voter education events, and promoted voter information on our Instagram and TikTok.

In a democracy, civic engagement is essential. Electoral politics shape the well-being of our communities. As I said in this interview, “participating in the democratic process is a vital way to maintain Randolph’s mission to engage the world, live honorably, and experience life abundantly.”

Feel free to check out our step-by-step voter registration guide.

08 May 2024

Check out this great new article about my time leading the American Culture Program.

Co-leading the American Culture Program has been a blast! The program is unique to Randolph College and is a great example of what makes Randolph special – small classes, experiential learning, and focused on ideas that matter.

For the last two years, we explored the intersection of labor, leisure, and music in the US. We traveled across town in Lynchburg, as well as to Charlottesville, DC, Knoxville, the Highlander Folk School, Memphis, and Nashville and met some amazing labor organizers, activists, musicians, politicians, scholars, and more! We several thought-provoking films, read some excellent books and articles, and had many lively conversations. The theme, “Working for the Weekend,” provided us all with the opportunity to reflect on what we want from our lives and how we can help make the world we want to live in. But it was also a lot of fun – I often described the American Culture Program as an opportunity to design my own “nerd vacation.”

Huge shoutout to my wonderful colleague Julio Rodriguez, our logistics expert Luisa Carrera, and to two great cohorts of students. And a massive thanks to the MANY people who we met with and learned from over the last two years.

You can listen to our collaboratively-created “Working for the Weekend” spotify playlist, review our 2024 syllabus, or see some more pics from our travels on our Insta.