15 May 2025

This year, I was honored to be selected for the Quillian International Scholar Study Abroad Seminar in Sri Lanka.

Last year, Randolph hosted Sri Lankan scholar Sudesh Mantillake as our Quillian Visiting International Scholar. I was fortunate to get to know Dr. Mantillake over the course of the year – his office was just down the hall from mine—and I was especially impressed by his performance of Kandyan dance in February, an event attended by the Sri Lankan ambassador.

Throughout the spring, the Randolph delegation followed a rigorous preparation schedule. We attended weekly information sessions on Sri Lankan history, religion, culture, and food, and many of us visited the Sri Lankan Embassy in D.C.

I also used this time to begin researching historical connections between the U.S. and Sri Lanka.

The first thing I discovered was that Sudesh was not the first Sri Lankan to perform Kandyan dance at Randolph! The R-MWC newspaper, The Sun Dial, reported that two members of the Ceylon National Dancers performed here in 1962. When I showed the image to Sudesh, he was blown away—the male dancer had been one of his mentors!

That discovery led me to wonder: Had Sri Lanka played a role in American religious history?

I started by thinking about the 1932 Hocking Report, titled Re-Thinking Missions: A Laymen’s Inquiry After One Hundred Years. I had first encountered it in David Hollinger’s Protestants Abroad, which highlights its pivotal role in reshaping Protestant missions and American Protestantism more broadly.

As a former Global Mission Fellow of the United Methodist Church—here’s my blog and podcast from those years—Hollinger’s arguments made total sense to me. It helped explain why I had such as radically different understanding of “mission” and a “missionary” than did evangelical Christians. In part, it’s because my tradition had been so influenced by the Hocking Report.

I discovered that the Laymen’s committee did indeed travel to Ceylon as part of their research. However, I wasn’t able to find any digitized sources detailing their time there. Ah the joys and challenges of doing social history…

A bit more internet digging led me to Howard Thurman as another possible link between American religious history and Sri Lanka.

I had read Thurman’s Jesus and the Disinherited in grad school and knew how deeply it had been shaped by his 1935 journey to India. During that trip, he met with Gandhi and helped forge a spiritual and intellectual link between Gandhian nonviolence and the American civil rights movement.

I also knew that his papers had been digitized through Boston University’s Howard Thurman Papers Project.

What I quickly discovered was that Thurman didn’t just travel to India—he also spent time in Ceylon (Sri Lanka) and Burma (Myanmar).

As I dug into his journal from his time in Ceylon, I began to see that Sri Lanka played a far more crucial role in shaping his ideas than I had realized.

I presented a paper on this research titled “Transformative Travel: Howard Thurman’s Pilgrimage to Ceylon and the Making of the U.S. Civil Rights Movement.”

Since I don’t anticipate publishing this research formally, I’m sharing the presentation text here.

18 Mar 2025

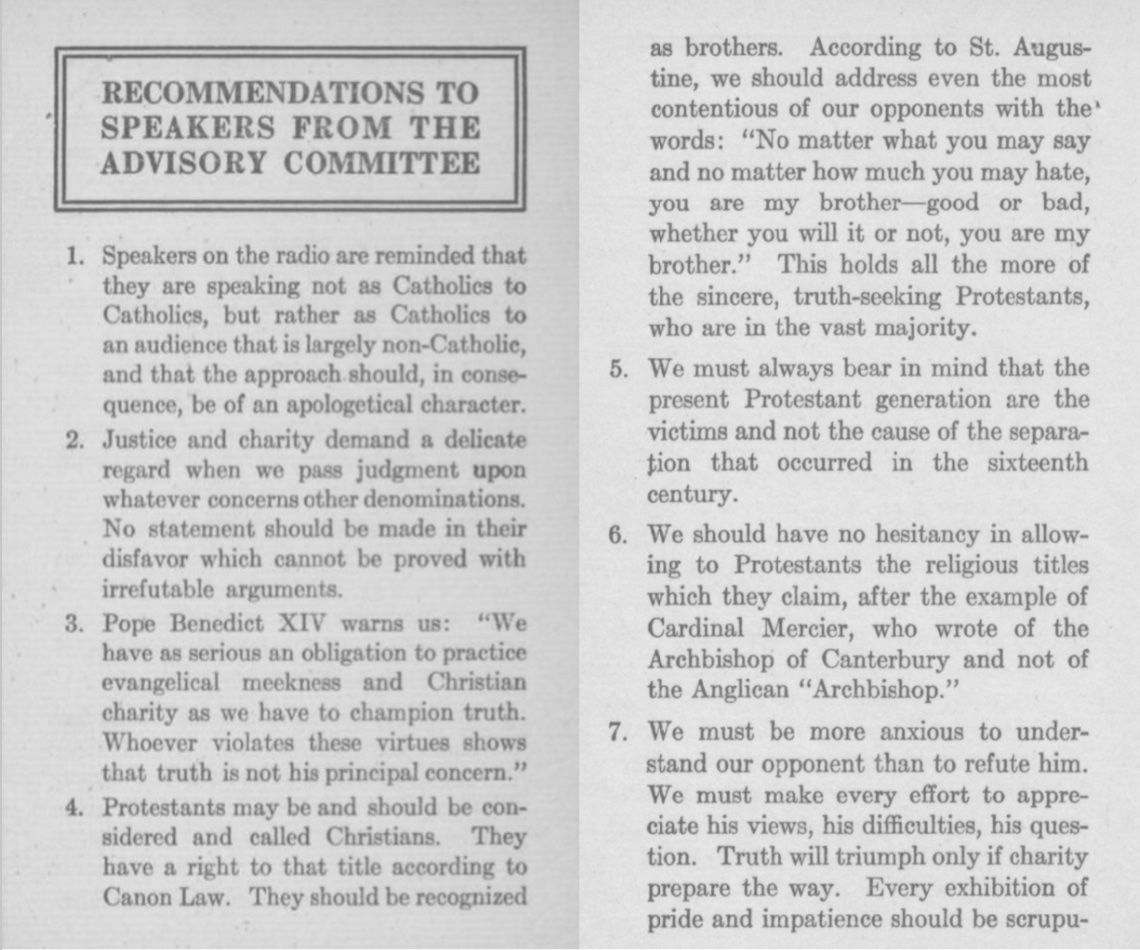

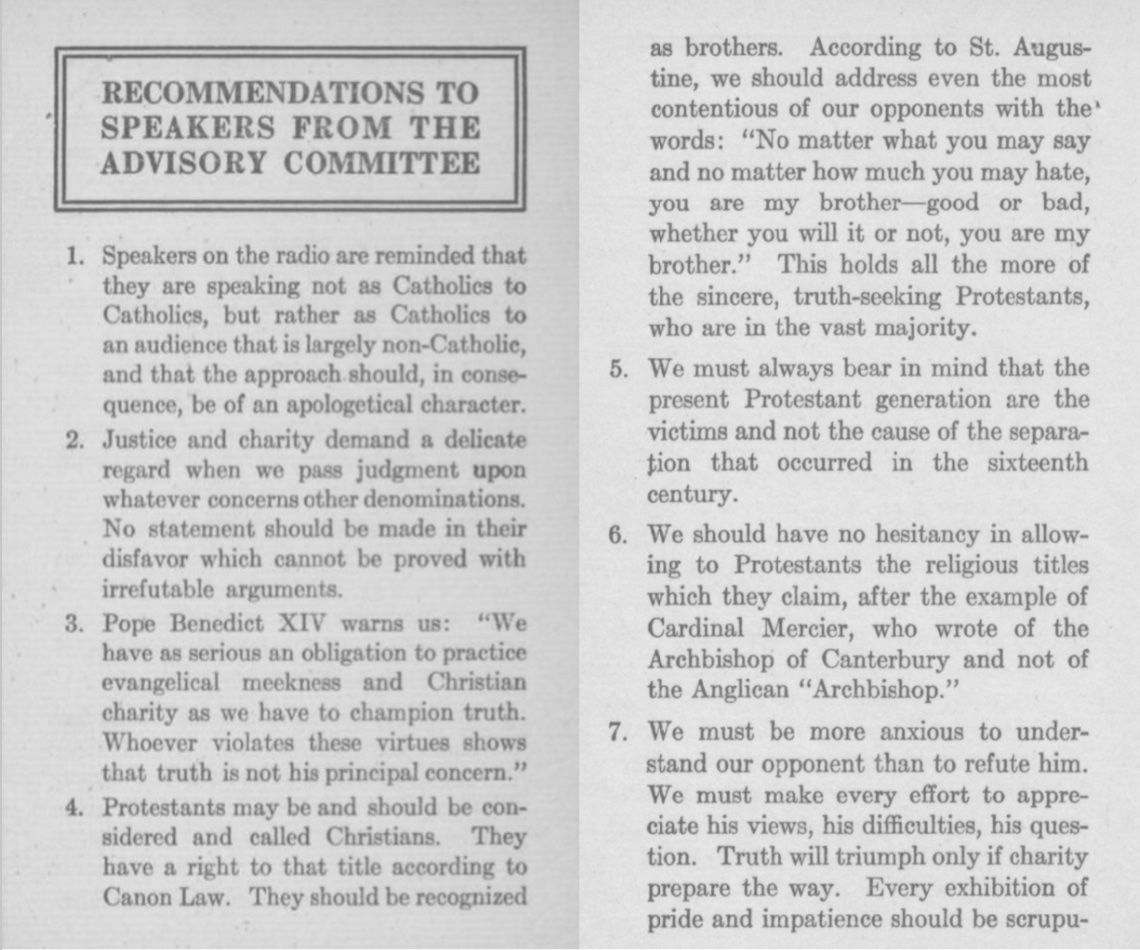

This spring, I headed to New Orleans to present a paper, “Forgotten Frequencies: Network Religious Radio and the Rise of Tri-Faith America.” The paper focused especially on NBC’s The Catholic Hour in the 1930s. The popular program emerged during an era rife with nativism and Protestant nationalism, and it powerfully demonstrated that Catholics could be both fully American and fully Catholic. Yet, to package Catholicism for a mass audience, Catholic organizers had to make strategic compromises that maintained Catholicism’s distinctiveness but didn’t offend non-Catholic listeners. This balancing act, I argued, helped pave the way for for Americans during and after World War II to see Protestants, Catholics, and Jews as co-equal pillars of American religious life.

Here’s a short Randolph News article about my paper: Kenaston Presents at Southeastern American Studies Association Conference.

21 Mar 2024

A few years back, I spent a few days at the University of Akron library digging into the Advertising Files of the Goodyear Tire & Rubber Company. I wanted to learn more about “Greatest Story Ever Told,” a religious radio program from the late 1940s and early 1950s that was later made into a TV program and a biblical epic. When Greatest Story emerged in 1947, it differed from all other religious radio programs at that time because it was sponsored by a commercial company.

As I was looking through Goodyear’s records, I came across several speeches and letters where Goodyear officials explained why they thought sponsoring a religious radio program was a good idea for their business. I was struck by how Goodyear used the tools of the advertising industry (eg, case studies, surveys, ratings, etc) along with an interfaith religious advisory committee (kind of like this one from the Coen brothers’Hail Caesar!) to tell the story of the Christian New Testament in a way that appealed to the mass market. As I was looking through the archive, I remember thinking, “Wow! I don’t know how to make sense of this yet, but this is really interesting!” Not long after that archive visit, however, I realized I needed to wrap up my dissertation prior to the start of WWII. So I set my findings on Goodyear and The Greatest Story aside.

I decided to return to those materials this fall, however. I wanted to test the waters to see if I wanted to stretch the timeline of The Big Three into the 1940s. I co-pitched a panel called “The Business of National Patrimony” to be presented at the Business History Conference in Providence, RI. My wonderful co-presenters were Dael Norwood and Whitney Martinko, and we were lucky to have Wendy Woloson as our commeter and Seth Rockman as our panel chair. Shout-out to Dael for doing most of the legwork in regards to getting the panel together!

My paper, “The Greatest Story: Commercial Radio and Religion in the American Century,” argued that Greatest Story Ever Told helped facilitate the rise of an imagined liberal consensus on religion during the Cold Year. At the same time, I also showed how the program’s well-publicizied innovative sponsorship model helped convince the FCC that commercial program could serve the public interest, leading to a foundational 1960 FCC ruling that enabled the rise of televangelism. I received some excellent feedback from both Dr. Woloson and from the audience that will help me revise.

This was my first time attending the Business History Conference, and I really enjoyed it. Special thanks to Randolph College’s Professional Development Committee for supporting my trip to Providence!